ISSN 2410-5708 / e-ISSN 2313-7215

Year 11 | No. 31 | June - September 2022

© Copyright (2022). National Autonomous University of Nicaragua, Managua.

This document is under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International licence.

Difficulties in the Culmination of Doctorals Thesis: Student´s voices

https://doi.org/10.5377/rtu.v11i31.14289

Submitted on 29 March, 2022 / Accepted on 05 May, 2022

Ph.D. René Antonio Noé

National Pedagogical University F.M., Honduras

Doctor in Professional and Institutional Development for Educational Quality

Diploma in University Teaching and Qualitative Research from the University of Barcelona, Spain.

Section: Education

Scientific Articles

Keywords: advise, difficulties, doctoral program, research, requisites, dissertation.

Abstract:

This article1 contains the results of a qualitative study conducted with doctoral students of four universities about the difficulties faced during the thesis writing process. Had as the main goal was to know the students´ perspectives regarding the factors that affect thesis writing. For the collection of data, we used an open-ended questionnaire. The results support that maintaining a balance between family, job, and thesis is the most complex of the difficulties faced by these students, and that job is fundamental to support family and studies, turning easier to set aside the thesis but not the job.

INTRODUCTION

In their eagerness to develop and propose a substantial contribution to society, universities are concerned every day to present training offers to society to respond in one way or another to the multiple problems that afflict their countries. For centuries now, universities have been offering bachelor’s degrees leading to bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral degrees. The latter is proposed by universities to offer studies of the highest level that could have international recognition, if possible. We recognize the learning process that involves researching and writing a thesis, therefore we are interested in knowing how the construction of the doctoral thesis forms the thesis as a researcher and producer of new theories and knowledge; however, as a priority, we are interested in knowing the difficulties faced by students throughout this process, but considered from the very voices of those who study these doctorates and build theses. Listening to them and valuing their contributions would allow programs and universities to have enough critical mass to make improvements and address these difficulties in such a way that the experience of doing a doctorate and writing the corresponding thesis, are significant and lifelong learning. In this study, we make a systematic review of the information available in previous studies and writings and we focus on identifying and defining the different difficulties present in the studies and then compare them with those identified, described, and valued by the doctoral students who participated in the study. , thus being able to establish a discussion that allows us to reach some conclusions. We emphasize that no one is better than the participating students to reveal the reality that is lived while writing the doctoral thesis.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Doctoral students constantly face situations that become problems, if they are not attended to in a timely and coherent way because they inhibit the work and slow down the realization of their research, reflected in a thesis or doctoral dissertation. The available literature points to different difficulties that are faced as progress are made in this training-research process. From the orientations of Jiranek (2010), we organize these factors according to entry requirements, personal characteristics, economics, abilities, and skills. In addition, we identify difficulties related to the institution referred to the assistance, direction, advice, tutoring, or supervision that should be available when doing a doctorate and those related to conditions, resources, and means available by the program.

Entry Requirements

Doctoral programs usually make a selection of students where some characteristics and capacities of a personal and academic nature are required. Indirectly, accepting anyone who applies without ensuring that they have some minimum skills can have an impact on the completion or not of the thesis. Previous studies indicate the importance of exhaustively determining these criteria, requirements, and merits (Jiranek, 2010) that candidates present for their future selection to the doctoral program. Sinclair (2004) points out that, sometimes, the selection of candidates for doctoral programs is not as rigorous as the requirements described, assuming that they end up accepting all pre-registered, either because they do not have enough applicants to start that course or because they are accepted. it must meet the times. Different universities have recommended that higher requirements should be required and better criteria should be practiced for selecting doctoral students (Manathunga, 2007 Ahern & Manathunga, 2004)). This would help improve terminal efficiency levels and ensure that students will complete their program and submit their theses on time (Rodwell & Neumann, 2008). Along the same lines, Castro et al. (2012), emphasize the importance of properly selecting the students who will do these doctoral studies. Additionally, we find that Sinclair (2004) argues that it does not differ from the perspective of supervisors or thesis directors, one of the problems that most affect completing the thesis on time is the selection of the students themselves. Additionally, when the thesis is not completed or subsequently graduated at the rate expected in the programs, it can be negatively reversed in the current applicants or new students, who when listening to or sharing the experiences of the current students, become demotivated and disoriented (Kohun & Ali, 2005; Hawlery, 2003; Lovitts, 2001; Bowen & Rudenstine 1992) going so far as to abandon, for not visualizing the benefits represented by all the investment and effort they make.

The challenges of entering a new academic culture and facing new ways of writing (Aitchison & Lee, 2007 Chanock, 2004), often frustrate the efforts of countless people who have ventured into this process of thesis construction ignoring the discipline or area of knowledge. These situations can lead to extremes of disorientation caused by trying to work in a field in which you have little experience and few references are known (Delamont and Atkinson, 2001 Carlino, 2012). Also, it may happen that these students, by not developing the skills required by the new academic culture, experience feelings and sensations that inhibit them from concentrating on research, reaching the extreme of isolating themselves (Kohun & Ali, 2005) and, consequently, abandoning their project.

A doctorate, as the highest academic degree to which an individual could aspire, represents an investment in which the person himself, his family, his resources and economic conditions, his social life, and his leisure time are put into play. However, doing a doctorate can be very rewarding and satisfying, this process requires the fulfillment of a series of requirements, the consolidation of skills and abilities previously learned, and the development of new competencies that will certify the expected training at this training level. Since the very decision to carry out these studies, students have faced a series of vicissitudes and difficulties that increase as they advance in their studies. Many of them have to do with very personal demands and we refer to habits, attitudes, behaviors, discipline, organization, finances, family situation, and health, among others. Likewise, analytical, synthetic, investigative, comprehensive reading, and writing skills are required, which are fundamental for the realization of work at this level.

From this perspective, some requirements are nested in the professional scenario or trajectory of the candidate such as contact with literature, reading culture, experience analyzing and processing information, and familiarity with specialists and referents who address the subject (Matsuda and Tardy, 2007) and the habit of writing and exposing ideas in a grounded way (Carlino, 2012), whose lack makes this formative process an imminent difficulty. By not having these competencies, skills, and abilities, doctoral students strive to reach extreme levels of personal demand (Manathunga, 2007), being able to become oversaturated by the scarce capacity for organization and planning they have, manifesting other behaviors related to feelings of vulnerability and anxiety, frustrating progress in thesis work (Carlino, 2012), finally opting to quit.

Undoubtedly, it is assumed that university students know how to write and consequently, the group of professionals who make a doctoral student, should do it better than in any other of the previous levels. However, the doctoral thesis leads to the rhetorical production of a new genre that requires a different way of writing (Carlino, 2012: 217). The development of this level of writing is the product of a conceptual and methodological domain in the subject, allowing them to generate their way of expressing their ideas and shaping their own academic identity. In this sense, Colombo (2014) argues that the “(...) doctoral students build a repertoire of strategies to successfully carry out scriptural demands while developing their academic identity (...)” (p.2). However, according to Carlino (2012), the writing process at this level must be more than a rhetorical and communicative practical form coinciding with the arguments presented by Flower (1979) and Hayes & Flower (1986) in this sense, who insist that one must have the requirement of academic production.

Time and Economic Demands

Doing doctoral studies requires a very serious investment of time on the part of the student body, which is why universities allocate part of their budget to the granting of scholarships or assistance so that these students can concentrate essentially on their research (Rodwell & Neumann, 2008; Sinclair, 2004; Tinto, 2003 and Lovitts & Nelson, 2000). Studies carried out in the United Kingdom, Australia and the United States reveal that the universities characterized by their research have a higher percentage of completion of theses and doctoral programs than those that are not (Sinclair, 2004). In the same way, the author argues that in these universities, 69% of doctoral students are scholarship holders or have funds from research, significantly helping to concentrate their research and completion of their theses.

The available literature holds that students who have a financial research grant or remain as fellows of a faculty or department tend to finish their thesis in less time than those who self-finance their studies (Jiranek, 2010 Green & Usher, 2003). To exemplify, Jinarek (2014) reports that of the 302 students who received scholarships at the University of Adelaide (Australia), “(...) the average time between their previous graduation and completion of the doctorate was 4.7 years, meanwhile, 74 students who did not receive a scholarship required an average of 6.1 years to complete[the]” (p.10). In addition, the concern is that even enjoying a scholarship, the completion of these studies is not assured as happens in Spain in the programs of training of university teachers (FPU) and training of research personnel (FPI) of which, the total of doctoral graduates does not exceed 50% (Buela-Casal, Guillén-Riquelme, Bermúdez & Sierra, 2011).

However, the reality of these doctoral students, in a high percentage, is that they make up a very particular population that can hardly attend exclusively their studies. They are people who work to self-finance and also support their own families and obligations and, in addition, work in organizations or companies that have already established their requirements. Consequently, attending to all responsibilities becomes a situation they face in their daily lives.

Professional Assistance and Qualified Personnel

Puche (2015) argues that the people who direct, supervise, tutor, or assist in the development of a doctoral thesis are fundamental pieces for the completion of it; however, universities lack staff who can devote themselves exclusively to these tasks or undervalue this work in those who perform it by making them apathetic to this need. Even though Ph.D. students fail to complete their theses represents an enormous cost to themselves (Jiranek, 2010; Meyer, Shanahan & Laugksch, 2005 and Gurr, 2001), from our perspective, turns out to be much more onerous for academia and researchers, as well as for universities per se (McAlpine & Amundsen, 2008; Prior & Bilbro, 2012, Carlino, 2012). We start from the fact that whoever directs, tutors, or supervises a thesis is a person knowledgeable in the subject and with methodological clarity for their research (Díaz, 2014). These staff, normally and depending on their seniority and career, have the privilege of choosing those whom they will direct or tutor during this process, ensuring pupils in whom they have seen the potential and tenacity and who almost assure that they will complete the research project. However, this situation generates chaos within the same academic networks because in the end they are left without tutoring, advice, and academic direction of high-level professionals those who need it most, forcing to a certain extent that the teacher with little experience and fewer qualifications, direct the student who until now has not excelled in his training process, in other words: “blind leading blind” as it would be expressed in biblical language.

It seems that it is lost sight of the fact that, even though the thesis, is a graduation requirement that, although it is true, marks the final stage of a training cycle, it must in turn be considered as that vital, affective experience and opportunity to identify new researchers (Golde, 2000; Ivanic, 2001; Boden et al., 2004; Cadman, 1994; Styles & Radloff, 2000; Vogler Urion, 2002 and Gurr, 2001), that is to say, that the qualified personnel to help in this direction must understand that they are immersed in a pedagogical process of broad learning (Díaz, 2014 and Jiménez-Mora, Moreno & Ortiz-Lefort, 2011) and the thesis is the culmination of that long process. Who directs must provoke wide spaces of communication (Manathunga, 2007 Gurr, 2001) so that the students advised, directed, or supervised do not evade or avoid fluid communication and do not produce personal isolation, in communication with the program, department, and staff that offers assistance (Khozaei, Naidu, Khozaei, & Salleh, 2015).

Facilities offered by the Programs

Many of the difficulties faced by doctoral students have their origin in the programs themselves, which do not offer the necessary conditions for students to work and complete their projects (Kohun and Ali, 2005; Golde, 2000 Lovitts, 2001). Additionally, doctoral programs must facilitate socialization with the program itself, its spaces, its staff, and resources available for use. Kruppa & Meda (2005) emphasize that the organizational socialization of the program is decisive to feel included and be part of the program. Another condition that must be offered as ease is certain lines of research, understood as backbones with a rational basis and continuous exercise in the production of knowledge (Meyer, Shanahan & Laugksch, 2005 and Agudelo, 2004 ). This facilitates the choice and delimitation of topics and the direct association between expert researchers and students and novice researchers. This would avoid the felt difficulty of assigning professionals to advise, direct or supervise research work (Tapia-Carlin, Méndez-Cadena, & Salgado-Ramírez, 2016). Additionally, the programs must generate that link between them with companies and with employment spaces, to ensure that students eliminate uncertainties regarding the opportunities they will have once they graduate.

OBJECTIVES AND QUESTIONS OF THE STUDY

This study specifically sought to know, from the perspective of the students, the factors that limit the completion of the doctoral thesis. In this sense, we identify the requirements demanded in the selection process; we define the difficulties faced by the students to choose and delimit the subject and to select or have a thesis director or supervisor; we describe the facilities they have both in their workplaces and on the part of the programs and we determine the greatest satisfaction and evaluations of the students regarding their study program and thesis writing process. Consequently, we ask questions among which we mention: What were the requirements that were demanded in the doctoral program?; What difficulties has it represented to do these studies? What facilities do you have in your workspaces and in your doctoral program to be able to fulfill your doctoral responsibilities and thesis completion? Among others.

METHODOLOGY

In this study, doctoral students from the University of Murcia (UMU), the National Autonomous University of Managua (UNAN-M), and the Francisco Morazán National Pedagogical University (UPNFM), and the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) were invited to participate. With the people who voluntarily responded to our request, a group of participants is formed. Two instruments were applied: a questionnaire of open questions made available to students through Google Forms and an in-depth interview conducted with those who requested it through Skype, Google Talk, Whatsapp video call, or personal interviews. The essential theme of the questionnaire and interview was the difficulties faced by doctoral students during the time they build their thesis. The same questions were used in both instruments. The questionnaire and conduct of interviews were conducted from January 2018 to April of the same year. Once the information collection period was closed, the corresponding analysis of the information provided was carried out.

The purpose of this study is eminently descriptive-explanatory. We seek to know in depth, from the perspective of the actors themselves, their experiences, difficulties, successes, failures, crises, and needs during the doctoral thesis. The method of constant comparisons was used (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) to find the meanings that the students gave to the difficulties encountered in the process. In some sections, we use the naturalistic paradigm to approach reality seen individually, understanding that each aspect analyzed is interrelated with the others by knowing the whole of this reality under study (Guba and Lincoln, 1982) and as far as possible, analyzing each case individually through the groups of students (Yin, 1993: Stake, 1978); however, the objective is concretized from the constant comparisons and triangulations of the contributions made by the students.

Research Instruments

The instruments for this research work are classified into three groups: 1) information collection, 2) information organization, and 3) analysis of information. For the collection of information, questionnaires with open questions were used, an instrument validated through the judgment of five experts from four universities. Once the assessments of four of the five experts were collected, we proceeded to redefine some of the questions raised, add elements that had not been contemplated and establish the direct relationship between the questions and the objectives of the study. The instrument was redefined considering these assessments and presented in its final format. It was transcribed in Google Forms to make the application of it online. A pilot test was conducted with PhDs and Ph.D. students from three universities to complete the validation and ease of storage in the Google Forms database. Once the testing and validation process was completed, it was sent to the study participants who had expressed their interest in participating in it. Mail was sent to 32 people among recent graduates, who had already deposited but not defended the thesis and those who were working on it, of which 17 responded, forming the group of participants. To organize the information, matrix tables were used (LeCompte, 1995), a coding to maintain the anonymity of the participants, and categorization (Glasser & Strauss, 1967) allowing to have clear the units of meaning for comparison and triangulation. (see Table 1).

Table 1

Question/Answer/Participant Code

|

No. |

1. What requirements were required for you to enroll in the doctoral program? |

Code |

|

1 |

Original postgraduate degree, personal documents, brief written on topics of interest for thesis research, the form of payment of studies. |

U1A |

|

2 |

Have a master’s degree. Present a letter of endorsement from the dean of FAREM where I work. Submit a letter of personal commitment to study. Present official cash receipt with the tuition paid. |

U2A |

|

3 |

Master’s degree with the degree duly incorporated in the UNAH 2. Experience of at least 10 years of work 3. Submit thesis work proposal 4. Academic index of 70% in the master’s degree |

U1D |

Note: Own Creation

The coding or nomenclature used, in the last column of the previous table, was defined to maintain the anonymity of the participants but clarity for the researcher when processing the information by the center and by each participant. U for the university, cardinal number to establish the order in which the educational centers participated, and the alphabet (A-Z) to establish the order of each participant.

The initial categories considered for the study were: requirements for admission to the program, choice and delimitation of the research topic, advice-direction-supervision, more felt difficulties, facilities in work centers, and facilities offered by the program; however, as we carried out the analysis, the issue of financing and scholarships emerged, as well as that of the family, work and thesis to which they gave special interest.

ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

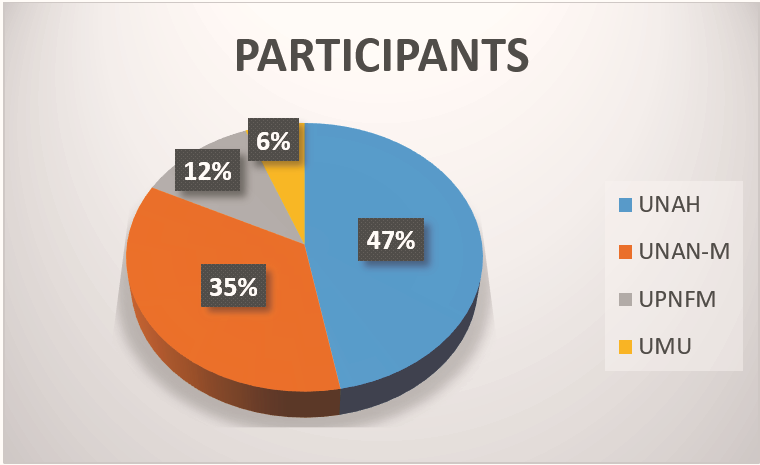

This section begins with the general characterization of participants in the study; secondly, the categories are taken into account and we value the contributions of these students to analyze each of them, using their own words thus allowing their voices to be heard in this study. (See Figure 1) .

Figure 1

Participants by University (Own Creation)

From UNAH 8, UNAN-M 6, UPNFM 2 and 1 from UMU. On the other hand, there was the help of two collaborators, who conducted the interview with U1F and sent the answers once the interview was over, as well as transcribed the audios sent by U3B. Of the total, ten women and seven men participated in distributed ages as shown in Figure 2.

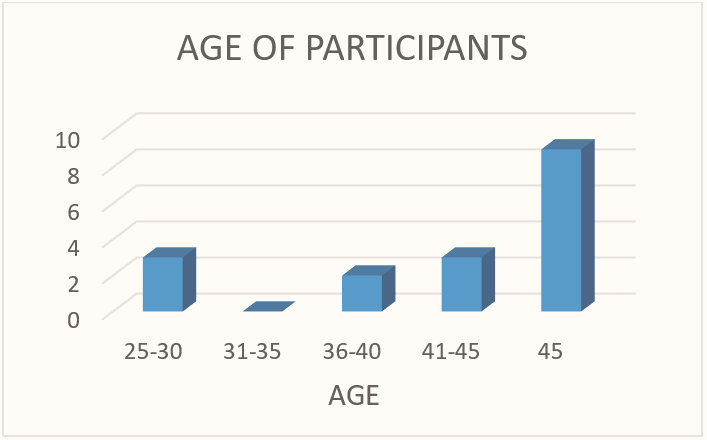

Figure 2

Age Ranges (Self-Creation)

The situation of the people at the time they participated in the study is distributed as follows: 8 of these (47.1%) have already completed all the modules and seminars but have not delivered the thesis; 7 recent graduates (41.2%) and 2 have already submitted the thesis but have not defended it (17.7%). Regarding the time they have to be in the program: 4 of these people (23.5%) are between 4-5 years old; 7 between 3-4 years (41.2%); 4 are over 6 years old (23.5%); 1 is between 5-6 years old and 1 is less than three years old, both with 5.9%.

Requirements for Entry

When analyzing the data reported by the students and recent graduates of the different doctoral programs we found that U1A, U2A, U2B, U2C, U2D, U2F, U1C, U1D, U1E, U1F, U1G, U3A, and U1H agree that they were required to have the master’s degree and present photostatic of it; likewise, participants U1A, U2A, U1B, U2F, U2G, U1F, U1G, U3A, and U1H indicate that they were required to write or essay on the subject to be investigated. One participant, U4A indicated that in its program, because it is a doctorate in Education, it was a requirement “To have a career in the area of education and research subjects”. Another requirement demanded by doctoral programs is the ability to pay (U1A, U2C, U1D, U1G, and U1H). The contribution of U1A includes all these requirements expressing that they had requested: “Original postgraduate degree, personal documents, brief written on topics of interest for thesis research, a form of payment of studies”. The academic index was reported as a requirement for U1B, U1C, U1F, and the entry application letter (U2A, U2C, and U2G), the mastery of another language is reflected by U2D and U1E. There are also other requirements among which we cite: attending classes punctually (U1H), a letter of endorsement from the authorities of the place of employment (U2C), and minimum work experience (U1C).

The findings reflect that to pursue a doctorate at the four universities, U1, U2, U3, and U4, the interested person must have at least a master’s or postgraduate degree duly supported, have written or pre-project research, demonstrate the economic capacity to cover the costs and, for U1, U2 and U3, have an academic index in his master’s degree not less than 70%.

When comparing these findings with other studies that address the issue of requirements we find that both Jiranek (2010), Ahern & Manathunga (2004), Sinclair (2004), and Manathunga (2005), agree that the success of doctoral programs depends largely on the selection processes of the aspiring students. In this sense, requiring mastery as an academic requirement to ensure the research competence and theoretical-conceptual mastery of their field of study, as recommended by Matsuda & Tardy (2007) and Carlino (2012), is essential to ensure success in the program.

These doctorates ensure that students have the financial capacity to bear the costs; however, they should manage a sufficient number of scholarships so that doctoral students can devote themselves exclusively to their research (Sinclair, 2004; Tinto, 2003, Green & Usher, 2003 and Lovitts & Nelson, 2000), in this way the culmination of the research process and subsequent thesis defense and the qualitative improvement of terminal efficiency as pointed out by Lovitts & Nelson (2000) and Tinto (2003) would be greatly ensured. Without losing sight of the fact that, having a scholarship ensures concentration on the study but not necessarily the culmination of the doctoral thesis (Buela-Casal, Guillén-Riquelme, Bermúdez & Sierra, 2011).

Delimitation and Interest by Topic and Program Help

According to the study, the time it takes to delimit the research topic varies from person to person, finding students who took just one month to people who took more than two years to define and delimit the topic. The interest in the subject has various sources such as their experience, their experiences, and their relationship with the work they performed; Likewise, they state that the program has helped them by guiding them in the choice of the topic and its delimitation, providing teachers to guide and direct the thesis and provide advice in the methodological area. U1A felt that choosing and narrowing down his research topic had taken him: “A long time, a couple of years!” He shares that he changed the subject and that his interest: “... it came from work practice.” But that the program, through its advice “... helped(... ) in the delimitation of the research problem”. On the other hand, U4A considers that the program director did not help to delimit its theme but that its directors have been fundamental to guide it. We detected in this contribution the dissociation between the provision of directors and the facilities offered by the program.

Existing literature (Jiranek, 2010; Amundsen, Weston, & McAlpine, 2008; Prior & Bilbro, 2012 Carlino, 2012) reveals that having a group of specialists to supervise and direct the theses is a fundamental value for students to complete their theses on time. In addition, this high-level staff allows us to understand that writing a doctoral thesis is a whole pedagogical research process where future teachers and researchers are being trained (Manathunga, 2002 Ahern & Manathunga, 2004) and that it helps to keep students focused on their project and connected to the program.

Time Spent on the thesis

Regarding the time it took them, has taken or continues to take their doctoral thesis, the answers and times vary from university to university and from student to student. The person who has spent the least time working on the thesis is U1H (a year and a half) and the one who has spent the most time on his thesis is U3A (about 8 years). Part of the student body believes that having the final document will take them two years (U2A, U2C, and U1C); for U2D and U2G two and a half years; between three years and five years it has taken U1B, U2B, U2F, U1D, U1G and U4A who have already finished. In summary, the thesis writing process does not have a definitive time, although it could be indicated in the descriptions of each doctoral program, but it is reduced or increased depending on the time of dedication, work, planning, and organization of tasks and personal, work and family commitments. However, the studies of Sinclair (2004), Ali & Kohun (2006), Ali, Kohun & Levy (2007), Manathunga (2005), and Castro et al. (2012) consider time to be a fundamental factor in the completion of theses and students need to be focused to complete their research in the planned times.

Director, Advisor, or Supervisor (Advice/Tutoring)

The process of selecting or assigning the person to direct, advise and supervise the research work has several nuances and ranges from people who consider that they do not have that guide and that the program has not helped at all, to people who value that it was a simple process and had all the support from the program. Additionally, we find that the time spent for this process ranges from one session to a year and a half to be able to select that person. Valorando the contributions, for U1A, U2A, U2C, U2F, U1D, U1G, and U3A, the process has been difficult reaching the extreme of not having the advisory person yet, of having had to change it due to lack of affinity or poor mastery of the subject. Also, U1G considers that the process to be followed for this person to be assigned is not understood. U2A complained saying, “I don’t have a thesis supervisor, I haven’t received support from the program.” U1D agrees with the above situation by adding, “The thesis supervisor topic is complicated, there is very little support on that topic.” or as U2C does say: “In my case, although I was assigned the tutor, he did not work in the education line and there were serious communication problems, so I did not receive enough support.”

However, particular cases reflect details that are worth highlighting: U2C expressed that when sending its advances the reactions from the advice was that: “... I had to consult him first, in case I had time to attend to my work.” Or the case of U1C it argues that it was somewhat difficult because they exceeded in communication via the Internet losing “rich discussions” or generating “misunderstandings”; it also considers a difficulty “The limited time of the advisors and sometimes their way of dealing (... )”, situations that have forced the change of guardian. But there are also cases like U3B who has not had an advisor to guide him and considers that each student: “(... ) must have an advisor to accompany him, which was not my situation and that is why it was more complex.”

Some studies give special importance to the figure of the supervisor, director, or thesis advisor (Amundsen, Weston, & McAlpine, (2008); Prior & Bilbro, 2012 Díaz, 2014) ensuring that having these people facilitates the situation by generating confidence and security in the student body; conversely, if the staff is scarce for this task, the students become demotivated and end up resorting to people with little experience in those particular fields of study.

Most Felt Difficulties When Writing Theses

The difficulties most felt by doctoral students are several and range from the way of writing (U1A and U1B), to the scientific confirmation of the work, through the organization (U1B and U2B), consistency or internal coherence (U2C and U2B), delimitation of the subject, lack of time for reading and writing (U2B and U3A), reading comprehension (U1C), limited equipment and technological domain (U2G and U1F), lack of thematic advisors (U1D, problems of writing and concretion of specific ideas (U1A, U2D, U1E, and U3A), scarce methodological mastery (U1G and U2B), self-discipline (U1H), little research experience (U1C, U1F and U3B) and the feeling of loneliness in which they find themselves (U4A). This participant said: “The worst thing for me is the feeling that you are alone. It is a very autonomous job and as such has negative aspects: it is you and your computer. When it comes to writing, it is simply having the day and the motivation to sit down and get the words (U4A).” Additionally, we find students for whom until the collection of bibliography has been a hard task, in that sense U2C expressed: “(...) Documentation is difficult, only in the search on specialized Internet sites and sometimes there is a problem with access. The purchase of books is required if necessary.”

However, the difficulty most felt by the whole group of participants is the articulation of daily work, personal life, family, and thesis, going so far as to conceive it as a sacrifice (U1A and U1B) and something very complex (U2F and U1H), which requires knowing how to balance, without basically neglecting work and family (U1A, U2B, U2G, U2C, U3A, and U1G) because it can end in divorce (U2D). Part of the students agrees that: work cannot be sacrificed because they depend on it both for family sustenance and the payment of their studies (U1A, U2A, U2B, and U2C), making it more reasonable to abandon the thesis because of employment (U2A and U1G). In conclusion, we use what U4A expressed for those who attend family, friends, work, and thesis “It is very sacrificed. You have to be clear that you want to do it (...) that you are passionate about and excited about the subject to investigate, if not, you can not do it. You have to put a lot of things aside to finish it.” On reflection, the existing literature reveals that these students should devote themselves essentially to their research (Rodwell & Neumann, 2008; Sinclair, 2004; Tinto, 2003 Lovitts & Nelson, 2000); however, the students participating in the study have very peculiar characteristics that require a balance between family, work and thesis without neglecting the first two. So far not much is known about that topic, but we consider that it deserves an in-depth investigation and the effect of that balance on the completion of the thesis.

Other Difficulties Identified

When inquiring about other difficulties and satisfactions faced by students working on their doctoral thesis we find the time and bibliography available, advice and good communication with advisory staff, knowing specifically what is expected of the doctoral thesis, conducting the field study, methodological domain, multiple responsibilities simultaneously and inconstancy or self-discipline. Exemplifying, U1C, U2B, U2D, U2F, U2G, and U1D refer to the fact of not having the time or not being able to dedicate the time required by the thesis. For U1C, U1A, U2C, and U1E little knowledge about research methodology are difficult; As well, for U2C, U2B, U2C, U2G, and U1F is not having available bibliography on the subject or methodology. On the other hand, U1B considers it a difficulty not to know exactly what is expected or what the thesis should contain. And in that same sense, U2B expressed that its difficulty lay in “[c]omprender the working approach of the thesis (...)”. U2C considers it a serious difficulty to maintain the necessary communication with its director. Additionally, we found two students who attribute the greatest difficulty to strictly personal conditions: U1H expressed that their inconstancy and indiscipline have made the task difficult and U3A point out that self-discipline and competence are required. investigative. In conclusion, the difficulties expressed are many; however, the fundamental problem is that doctoral programs have been proposed for people with almost exclusive dedication to their studies and the typology of this student body shows that this is impossible for them. The types of the student body and terminal efficiency in doctorates should become a subject of study.

Satisfactions of this Formative Process

On the other hand, the greater satisfaction that these students have experienced throughout their studies revolves around their personal, scientific, and professional evolution. From a personal perspective, U1B is proud of the topic it investigates; U2B valued his learning and expressed “(...) I know what I want to do and how I want to do it”; they also reflect great satisfaction with their learning U1A, U1B, U2C, U2D, U1C, U2F, and U4A. Additionally, his scientific and professional evolution among the greatest satisfactions is expressed by U1A, U2B, U2C, U1C, U1F, U1G, and U4A, for whom he is also satisfied to have met and been meeting other people, realize his limitations and trust that the doctorate will open better opportunities.

Working on the doctoral thesis, despite the ups and downs that it contemplates, is valued by U1B as a fantastic and extremely difficult experience that leads to comprehensive training. U1A described it as a life experience that leads to maturity and perseverance. For U2C, working on the thesis developed “(...) love of knowledge, social commitment, and tenacious work.” U3C expressed that having done his doctorate and working on his thesis was on “experience (...) formative, challenging and satisfying.” Finally, U4A adds that doing your Ph.D. and writing the thesis consists of a “(...) process full of fear, feeling passion [and] not losing sight of your goal.”

Sintetizing, writing the thesis combines, according to U2B: “Personal life, the killer stress of fulfilling work coordination assignments, direct planning and teaching, internal and external meetings, early morning and late night wakefulness.”

Facilities in Work Center and Program

The facilities provided by the institutions or organizations for which the students work, we find expressions that reflect a lot of support even those that consider that obstacles and obstacles have been put in place forcing them to breach their responsibilities of the doctorate and their thesis work. First, we found students whose companies granted them some type of scholarship from 50% (U1A, U2C, U2G) to 75% (U2B); one person applied for their research grants to finance their studies (U1E); and another who maintains that he received financing facilities (U1C) but that in the end, his debt was greater because they could not complete studies within the established term of five years. The organizations granted permits to attend the courses, seminars, and modules of the program (U1A, U2A, U1B, U2B, U2C, U2D, U2G, U1F, U1G, U3A, and U4A); however, once the face-to-face sessions were over, they did not have the necessary permits to work on their thesis (U2A and U1B). Additionally, we found two cases in which it is reflected that the institutions where they worked instead of presenting facilities put obstacles in their way. U1C expressed that the University was its employer and that: “... rather they put us in trouble and the financial support was charged at twice what the doctorate cost (...) They imposed more academic burden on us, there were no permits to study or to do the thesis.” When reflecting on this topic, we do not find much-existing literature, but it would be interesting to know the value that companies give to studies such as doctorates and how companies help or inhibit the realization of them.

Regarding the facilities made available by the doctoral program we find part of the student body that values the attention they receive to their queries (U1A), bibliographic support (U1A, U1E, and U3A), thesis advice (U1A, U2C, and U3A) and workshops (U2D and U1F); likewise, we find that for U1G: “The program does not make many tools available, in general, this is an effort of its own.” And some argue that although there were facilities on the part of the program, the conditions of the students do not allow them to take advantage of them. For U4A, to some extent, the program has been very hard because when you miss only one of the meetings, seminars, or workshops, the policy of that is to lose it completely, being forced to request more time permission to be able to repeat them. U3B explained that the doctoral program does not offer many options, the available bibliography is scarce and not updated, and the incipient infrastructure and the very limited technological conditions force everything to be agency in a personal way.

The companies provide help to doctoral students through scholarships, permits, changes of schedules, and bibliography among others; however, it does not happen in all cases and the university “U1” turns out to be the one that has made the least facilities available to students. On the other hand, the programs of the different universities provide bibliography, advice, and openness to consultations and workshops but these facilities they offer do not contemplate the conditions of the doctoral student, who have to comply with working days that make it difficult for them to benefit from these advantages due to the schedules or restrictions for the use of them.

CONCLUSIONS

Once the study is finished, evaluating all the evidence and trying to answer the questions raised at the beginning of it, we allow ourselves to conclude the following:

Regarding the requirements or demands of universities to be able to access a doctoral program, the findings reflect that to pursue a doctorate in U1, U2, U3, and U4, the interested person must have at least a master’s or postgraduate degree duly supported, present pre-project research, demonstrate economic capacity and a 70/100 minimum performance in previous studies. In general, there is evidence to express that these requirements are necessary but not sufficient to ensure that the students will complete the program and present the doctoral thesis and that they should be more rigorous and demand professional and personal skills of the students for this degree of studies such as analytical and scientific reading, writing and writing level and research experience.

Concerning the difficulties faced by the students, the findings reflect that the greatest difficulty faced or has faced by these students is coordinating work, family, and studies forcing them to establish priorities that could threaten the continuity and persistence in the program or the very stability of the families. Likewise, the participants reveal other difficulties ranging from the financing of their studies, scarce time to devote to research work, the difficulty of not having staff for advice, direction, and supervision of theses, ignorance of research methodologies, limited available bibliography and access to sources of information, condition it is personal of the students and technical-technological resources that they make available in the programs but in schedules and times not accessible to the student body.

Regarding the facilities they have received from companies or workplaces, we find that this group of participants assure that they have had permits to attend their seminars, workshops, and conferences, have made arrangements during the working hours, and have been granted financial aid for the payment of their studies; however, there is also evidence to think that students who work in universities tend to enjoy some perks such as loans for studies, unpaid leave but not scholarships for exclusive dedication to studies. In addition, the students who work in the universities, reveal that the university supports with the permits making the schedules more flexible but only do it while the modules, workshops, and seminars last, but that once the thesis work has begun, they do not have that type of support feeling overwhelmed by their workload that forces them to dedicate themselves almost exclusively to teaching.

On the subject of study, delimitation, and choice of the person who directs, supervises, advises, or tutors the research work, the results of this research reveal that it is essential to delimit the subject but above all to have that person to guide them promptly, in an environment of respect and trust; however, They complain because these resources are insufficient and the staff is scarce, forcing them to even attend to issues that are not of their specialty.

Around the most felt difficulties, we pointed out above that the coordination of family, work, and study is the most difficult and requires a magnificent organization and management of time and resources so as not to neglect any of them. Likewise, the students reflect as enormous difficulty the lack of experience in the field being investigated, little time available to devote to research, and economic situations that overwhelm making it easier to abandon the thesis than work, because providing for the home is a priority.

The satisfaction felt by this student body allows us to assess the evolution achieved in a personal and scientific-professional way, the true learning process in which they participate, the overcoming of fear and uncertainty as always present elements, and that the passion for that work allows not to lose sight of the goal and crown it with the presentation of this thesis. Finally, the process that is followed to build a thesis is not easy, nor simple but completing it is a source that fills with satisfaction not only for those who do it but also for all those who in one way or another participate in it.

Footnotes

1. Research article that is part of the research line on “The Development of Scientific Research”. It is a counterpart to the Cruz del Sur Project proposals by the Francisco Morazán National Pedagogical University (UPNFM), https://cruzdelsur.um.es/, Project Number: 551456-EM-1-2014-1-ES-ERA MUNDUS-EMA21. Post-Doctoral Stay at the University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain.

Bibliography

Acker, S. (2001) The hidden curriculum in dissertation advising In E. Margolis (Ed.) The hidden curriculum in higher education, pp. 61–77, New York Routledge.

Agudelo, N.C. (2004). The lines of research and the training of researchers: a look from the administration and its training processes. Revista ironed: electronic journal of the educational research network, Vol.1, No. 1, p. 11. Retrieved October 2018, from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2004902.

Ahern, K. & Manathunga, C., (2004). Clutch-Starting Stalled Research Students, Innovative Higher Education, Vol. 28. pp. 237-254.

Ali, A., & Kohun, F. (2006). Dealing with isolation feelings in IS doctoral programs. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-33.

Ali, A., Kohun, F., & Levy, Y. (2007). Dealing with Social Isolation to Minimize Doctoral Attrition- A Four Stage Framework. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 33-49.

Amundsen, C., Weston, C., & McAlpine, L. (2008). Concept mapping to support university academics’ analysis of course content. Studies in higher education, Vol. 33, No. 6, pp. 633-652.

Andresen, L. (2000). Teaching development in higher education as scholarly practice: A reply to Rowland et al. ‘Turning academics into teachers?’. Teaching in Higher Education, Vol. 5, pp. 23–31.

Buela-Casal, G., Bermúdez, M., Sierra, J., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Castro, Á., & Guillén-Riquelme, A. (2011). 2010 Ranking in research production and productivity of Spanish public universities. Psychothema, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 227-236.

Carlino, P. (2012), Helping Doctoral Students of Education to Face Writing and Emotional Challenges in Identity Transition. En Castello, M. y Donahue, C. University writing: Selves and Texts in Academic Societies. London (Reino Unido): Emerald Group Publishing.

Carlín, R., Cadena, M. & Ramírez A. (2016). The doctoral thesis as a space for academic, professional and personal development: Beliefs of researchers. Option: Journal of Human and Social Sciences, Vol. 13, pp. 1001-1027.

Castro, Á., Guillén-Riquelme, A., Quevedo-Blasco, R., Bermúdez, M., & Buela-Casal, G. (2012). Doctoral Schools in Spain: Suggestions of Professors for their Implementation//The Doctoral Schools in Spain: suggestions for their implementation based on the opinion of civil servant professors. Journal of Psychodidactics, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 119-217.

Glaser, B. & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine Press.

Golde, C. (2000). Should I Stay or Should I Go? Student Descriptions of the Doctoral Attrition Process. The Review of Higher Education, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 199-227. doi:10.1353/rhe.2000.0004.

Green, P., & Usher, R. (2003). Fast supervision: Changing supervisory practice in changing times. Studies in Continuing Education, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 37-50.

Guba, E. & Lincoln, Y., (1982). Epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry. ECTJ 30, pp. 233–252 https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02765185

Jiranek, V. (2010), Potential Predictors of Timely Completion among Dissertation Research Students at an Australian Faculty of Sciences, International Journal of Doctoral Studies, Vol. 5, pp. 1-13.

Kruppa, R., & Meda, A. K. (2005). Group Dynamics in the Formation of a Ph.D. Cohort: A Reflection in Experiencing While Learning Organizational Development Theory. Organization Development Journal, Vol. 23, Issue 1, pp. 56-67.

LeCompte, M. (1995). A convenient marriage: qualitative research design and standards for program evaluation. RELIEVE-Electronic Journal of Educational Research and Evaluation, Vol. 1, No.1, pp. 1-13. Consulted in http://www.uv.es/RELIEVE/v1/RELIEVEv1n1.htm

Lovitts, B. & Nelson, C. (2000). The hidden crisis in graduate education: Attrition from Ph. D. programs. Academe, Vol. 86, No. 6, pp. 44-50.

Lovitts, B., (2001). Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Manathunga, C. (2005). Early warning signs in postgraduate research education: A different approach to timely completions, Teaching in Higher Education, Vol. 10, pp. 219–233.

Matsuda, P. & Tardy, C. (2007). Voice in academic writing: The rhetorical construction of author identity in blind manuscript review. English for Specific Purposes, No. 26, Vol. 2, pp. 235-249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.10.001

Meyer, J., Shanahan, M., & Laugksch, R. (2005). Students' Conceptions of Research. I: A qualitative and quantitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, Vol. 49, No. 3, pp.225-244.

Prior, P. & Bilbro, R. (2012). Academic enculturation: Developing literate practices and disciplinary identities. University writing: Selves and texts in academic societies, pp. 19-31.

Rodwell, J., & Neumann, R. (2008). Predictors of timely doctoral student completions by type of attendance: the utility of a pragmatic approach. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 65-76.

Sinclair, M. (2004) The Pedagogy of 'Good' Ph.D. Supervision: A National Cross-Disciplinary Investigation of Ph.D. Supervision, Faculty of Education and Creative Arts, Central Queensland University, Canberra, Australia.

Stake, R. (1978). The case study method in social inquiry. Educational researcher, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 5-8.

Tardy, Ch. and Matsuda P. (2009). The Construction of Author Voice, Written Communication, Vol. 26, No. 1, January, pp. 32-52.

Tinto, V. (2003). Learning better together: The impact of learning communities on student success. Higher Education monograph series, Vol. 1, No. 8, pp. 1-8.

Yin, R. (1998). The abridged version of case study research. Handbook of applied social research methods, Vol. 2, pp. 229-259.