ISSN 2410-5708 / e-ISSN 2313-7215

Year 12 | No. 35 | October 2023 - January 2024

© Copyright (2023). National Autonomous University of Nicaragua, Managua.

This document is under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International licence.

Levels of emotional intelligence in students of EFL, FAREM-Matagalpa: case study

https://doi.org/ 10.5377/rtu.v12i35.16995

Submitted on 14 th March, 2023 / Accepted on 22 th September, 2023

Julio César Roa Rocha

National Autonomous University of Nicaragua-

Managua, FAREM-Matagalpa, Nicaragua.

Section: Humanities & Arts

Scientific research article

Keywords: Emotional Intelligence (EI), English language teaching, Higher education, Learning abilities, language performance, Speaking ability.

Abstract

The following article presents advances of a doctoral study, whose objective is to evaluate the levels of emotional intelligence of the students of the Education Sciences with mention in English of FAREM-Matagalpa. This study used a mixed quantitative-qualitative approach. For data collection purposes, a test to estimate the level of emotional intelligence was administered to 25 students, considered a unit of analysis within the case study strategy. The test was composed of 30 statements on a Likert-type scale. For analysis purposes, a numerical and qualitative value was assigned to the responses. The overall findings indicate that students have emotional skills that allow them to be aware of their goals and emotions for English language learning.

INTRODUCTION

Within the teaching-learning process of a second language, there are different levels of language acquisition and proficiency. There are, therefore, differences that allow us to deduce that some people learn more easily and others have greater difficulty. Among so many factors that contribute to success in learning a second language, including motivation, attitude, or personality types, it seems that an important factor that explains success in language learning is the degree of emotional intelligence (E.I.) that people possess (Pishghadam, 2009).

In this regard, Vygotsky (1979) emphasizes that the emotional factor somehow conditions learning. That is to say that emotions predispose the student to a type of response or reaction, which is linked to the emotional memories learned in the different educational environments in which the student has participated.

In this sense, it should be recognized that education, for many years, has placed its epicenter in the development of cognitive aspects, but little is known about the emotional skills that students possess or acquire in their learning environments. Goleman (1998) explains that “academic or intellectual intelligence has little to do with emotional intelligence” (p.35). In other words, academic achievement does not necessarily indicate that the individual can face and solve real-life problems introspectively or extrospectively, but rather that other elements are required for the resolution of real-life situations.

Research on emotional intelligence as a field of study in second language learning dates back to the 1970s, particularly in English in countries where it is different from the mother tongue. Since then, there has been increasing research to show that emotional intelligence is important, like other intelligences, in many aspects of people’s lives, and significantly in second language learning ( Abdolmanafi Rokni, SJ, et al., 2014).

For example, in English language learning, motivation is fundamental for the affective and effective development of the student in the construction of their learning and acquisition of autonomy within their training process. When a student is motivated, he seeks other learning alternatives, gives meaning to what is around him, and makes use of his capabilities and potential allowing him to overcome his difficulties (Gutiérrez, 2020).

The purpose of this study is to investigate the role of emotional intelligence I.E. in second language learning. For this purpose, it is intended to assess the emotional skills possessed by first-year students (juniors) of the degree in Educational Sciences with a major in English at FAREM-Matagalpa, recognizing that emotional intelligence is a valuable element in the learning of the English language that frames other dimensions within it and that few investigations allude to this topic at a higher level, especially in the field of teacher training in the Nicaraguan context. The purpose of this study is to propose didactic actions to improve the English learning process in teacher training.

Theoretical framework

Learning a second language can be considered a difficult, exhausting, and stressful task for some learners, particularly for adults, who may face great difficulties in their attempts. In general, it could be said that, for some people, it is easy to articulate a foreign language without major drawbacks, while, for others, they always seem to fail or show little progress despite all the efforts they make (Zarezadeh, 2013).

Intelligence levels play an important role in their learning of English; however, their success or failure is not limited to intelligence level alone. Recently, psychologists have pointed out another avenue that includes I.E. in education. According to Goleman (1998), a distinguished and expert psychologist in the field of emotional intelligence, 80% of the reasons for any success can be attributed to emotional intelligence, since affective factors play a relevant role in learning in general and language learning in particular, (Goleman, 1998).

The findings of this study can be of great help to teachers. Emotional intelligence instruction will enable weak learners to improve their understanding and production of emotions, understand personal and others’ feelings, sympathize with others, and manage stress (Ramirez, Espinoza, Esquivel, & Naranjo, 2020).

Some methodologies specifically address emotional and psychological issues in second language learning. However, until now, few studies have investigated the role of emotional intelligence in foreign language learning (Pishghadam, 2009). Due to the paucity of research on E.I. and foreign language learning, this study seeks to shed light on the relationship between emotional and verbal intelligences and success in second language learning (GPA, reading, writing, speaking, and listening) (Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995).

The problem that gives rise to this study is the paucity of evidence about the relationship between a teacher with low E.I. who cannot expect to increase the emotional intelligence of his or her students. Teachers’ emotional intelligence must be promoted so that students learn better. Several research studies (Ramirez, Espinoza, Esquivel, & Naranjo, 2020) indicate that the current educational system focuses on cognitive aspects and not on the emotional mind.

Emotional Intelligence Theory

Emotional intelligence is not a new topic. It is based on a history of personality theory and social psychology. Since 1990, when emotional intelligence was first introduced, it has become a usual term in psychology and has been used in many fields, including education, management studies, and artificial intelligence (Ocaña, 2011). The history of emotional intelligence began with the meaning of social intelligence, understood as the ability to empathize with others and behave correctly in social relationships (Zarezadeh, 2013).

The theory of emotional intelligence was first developed by psychologists such as Howard Gardner, Peter Salovey, and John Mayer during the 1970s and 1980s (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000). Gardner asserted that older IQ tests only measure language and logic, not other skills, since we know that our brains also have other brilliant types of intelligence (Gardner, 1983). Gardner discussed that human beings have these intelligences, but differ in strengths and combinations of intelligences. He said that all of them can be achieved by training and practice. Intelligence can be improved by environments and experiences; it is an innate capacity of the individual.

Emotional intelligence is part of the large group called multiple intelligences (MI). Gardner (1983) introduced eight different types of M.I. intelligence in his works, namely, linguistic/verbal intelligence, logical/mathematical intelligence, musical/rhythmic intelligence, kinesthetic/corporeal intelligence, spatial/visual intelligence, naturalistic intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, and intrapersonal intelligence (Gardner, 1983). One of these intelligences was personal intelligence (inter and intra) which later developed as emotional intelligence. Finally, in 1990 psychologists Mayer and Salovey, based on Gardner’s vision, developed and introduced the complete model of emotional intelligence (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000).

Emotional intelligence is a combination of the terms emotion and intelligence (EQ). Emotions are one of the three fundamental classes of mental operations consisting of motivation, emotion, and cognition. A person in a good mood thinks positively and is productive and vice versa. Therefore, E.I. means that emotion and intelligence are related to each other ( Abdolmanafi Rokni, SJ, et al., 2014).

Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Language Learning.

In the past, individual differences such as E.I. were ignored to play a role in teaching and learning a language, but studies revealed that in addition to the role of IQ, E.I can also play a role in this system (Zarafshan & Ardeshiri, 2012). Gardner (1993) explained that to fully understand the complexity of the language learning process, we must pay attention to the internal mechanisms and interpersonal social interactions involved in this process.

Daniel Goleman (1998), the leading spokesman for I.E., argued that approximately 80% of the variation among people in various forms of success that is not explained by I.Q. tests and similar tests can be explained by other characteristics that constitute I.E. He has defined I.E. to include “skills such as being able to motivate oneself and persist in the face of frustration, controlling impulses and delaying gratification; regulating mood and preventing distress from impairing thinking ability; underlining and waiting” (1998, p. 34).

Students with higher IQ scores are considered more intelligent, but recent studies showed that E.I. can be more powerful than IQ (Abdolmanafi Rokni, SJ, et al., 2014), i.e., the effect of emotions on learning can be positive or negative. However, the effect of emotional intelligence on the learning experience is positive and can promote good study behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, non-experimental research was used, under a mixed approach. That is, the phenomenon was worked without any manipulation by the researcher. The dominant method was quantitative with qualitative incidences (Hernández, Fernandez, & Baptista, 2014).

The strategy used within its methodological design in this research is the case study. The case study attempts to understand the subject being studied holistically within its reality. The case study has the flexibility to use qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques (Yin, 1994). This research used the intrinsic case study, to know the case in depth according to Stake, (2005). It is worth mentioning that, this study attempts to particularize what happens to the investigated object within its natural context.

The participants in this study are first-year undergraduate students of the Bachelor’s Degree in Educational Sciences with a major in English who began their studies in the first semester of the year 2021, at a UNAN-Managua campus, named FAREM-Matagalpa. At this stage of research, the students were finishing their second year of study. Therefore, the choice of the case is justified by the following criteria: ease of access to the group of students, under study, the possibility of establishing a good relationship with the informants and, in this way, obtaining a complete understanding of the reality that the participants live. It should be noted that 25 students (9 women/16 men) participated in this stage of the research, out of a group that started with 42, of which 17 have withdrawn from the course.

The data collection technique implemented was the application of an emotional intelligence test to know the emotional level of the students. The instrument designed was a test composed of the dimensions: intrapersonal intelligence and interpersonal intelligence, under the following subdimensions: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy, and social skills. These subdimensions corresponded to the following indicators: confidence, self-assessment, conscientiousness, trustworthiness, self-control, openness, instrumental motivation, integrative motivation, understanding, and conflict management. Each of these indicators has its respective descriptors.

The emotional intelligence test contained 30 descriptors on a Likert-type scale (see Appendix A). The EI test was constructed using the following three validated, standardized tests as a basis, and it was adapted to low English language learning:

1. Trait Meta-Knowledge Scale on Emotional States, based on the Trait Meta-Mood Scale by Salovey and Mayer (1995), composed of 48 questions, English version.

Spanish version of Salovey and Mayer’s test, composed of 24 questions, by the authors Fernández Berrocal, P.; Alcaide, R.; Domínguez, E.; Fernández-McNally, C.; Ramos, N. S.; Ravira, M. (1998).

Emotional intelligence test developed by José Andrés Ocaña (2011) in his book “Mapas mentales y estilos de aprendizaje” (Ocaña, 2011).

The E.I. test was validated by experts in the field of psychology and reviewed by English and education teachers, piloted with a group with similar characteristics for improvement purposes before being applied to the target group. The test was subjected to a validity and reliability analysis in SPSS software, using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, which resulted in 0.882, indicating that the reliability of the items examined is “good”.

The Google Forms format was used, which was shared through the WhatsApp group. Data obtained from Google Forms were collected, generating an Excel database for statistical analysis. A descriptive analysis was performed for the study variables, determining frequencies and percentages. To process the information and generate the graphs, Microsoft Excel 2017 and SPSS were used.

For this purpose, an arithmetic value was assigned to the Likert frequency scale levels. Then, a final summation was performed between the selected responses and the scales. This made it possible to place the scores according to their levels and their qualitative value to know the emotional intelligence levels of the participants.

The information explained above is presented below:

Table 1

Numerical and qualitative value of emotional intelligence tests

|

Never |

Sometimes |

Almost always |

Always |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Numerical value |

Levels of emotional intelligence |

Qualitative value. |

|

30≤ x ≤ 59 |

Low emotional intelligence |

This score indicates that your emotional skills are still low. You need to know yourself better and value your capabilities of what you are capable of. |

|

60≤ x ≤ 89 |

Medium emotional intelligence |

This score indicates that your emotional skills are close to desirable. That is, you manage your emotions, you have good communication with other people, you know a lot about what you think, do, and feel, you understand how others feel, and you maintain good relationships with them. |

|

90≤ x ≤ 120 |

High emotional intelligence |

This score indicates that your emotional skills allow you to be aware of yourself, your goals, and your emotions. Also, it indicates that you can communicate successfully with the people around you and know how to value yourself. |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The data obtained from the administration of the emotional intelligence test are presented below.

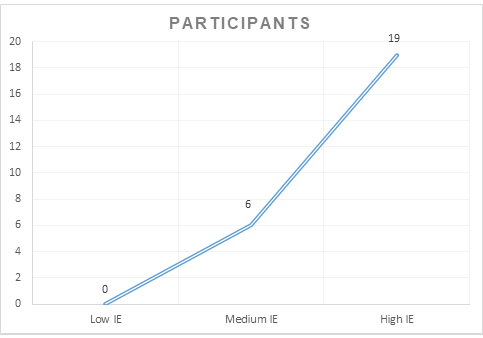

Figure 1

Information obtained from the emotional intelligence test.

Figure 2

Level of E.I. reached

Source: Own elaboration: Own elaboration

According to data in Figure 1, 76% of the FAREM-Matagalpa students who took the test reached a level of emotional intelligence considered high, which, according to the descriptors proposed in this study, the students have the emotional skills that allow them to be aware of their objectives and emotions. Their communication skills are satisfactory with the people around them and they possess a high self-esteem.

Dewaele (2018) opines that positive emotions are of much consideration to achieve meaningful learning (cited in Méndez, 2022). It should be recognized that “a person considered emotionally intelligent possesses the necessary skills to cope with various stressful situations more successfully than one who is not” (Mendez, 2022).

In this regard, Zarezadeh (2013), conducted a study with 330 students of English literature and English as a foreign language, the author found that emotional intelligence plays a fundamental role in speaking ability. She emphasizes the role of intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligence in the state of mind students have when communicating.

Fredrickson (2001) in his theory on positive emotions, explains that certain positive emotions facilitate the discovery of new knowledge. In learning English, to cite an example, an investment in the personal strengths of the learner is required to expand mental action (cited in Kushkiev, 2019).

On the other hand, in this study, 24% of the students reached a medium level, which means that according to the proposed descriptors, the students possess emotional skills close to the desirable or considered high emotional intelligence level. That is, they manage their emotions, have good communication with other people, know much of what they think, understand how others feel, and maintain good relationships with them.

The acquisition of positive emotions in higher education, according to Luy-Montejo (2019), provides students with “the ability to establish positive interrelationships with peers, the ability to resolve incidents, cooperative work, openness and desire to change or thinking based on innovation” (cited in Gutiérrez, 2020, p.19).

Up to this point, it is worth mentioning that, of the 6 students who reached a medium level of emotional intelligence (see Annex B), according to Roa (2022), they obtained a basic A1 level of linguistic proficiency in the diagnostic test of English language skills, which was carried out in the first stage of this research, which could indicate in some way that these students are in the process of reaching the emotional skills considered high and better linguistic performance in English language skills (Roa, 2022).

Concerning the above, Krashen (1983) in his natural order hypothesis, explains that in the acquisition of a language, there are processes considered natural, which happen in a certain order, for example, grammatical structures and rules (cited in Kushkiev, 2019). Based on this hypothesis, it can be inferred that students will reach better levels of emotional intelligence and linguistic performance as they interact with higher learning, which requires other emotional as well as linguistic skills.

To conclude this section, it is worth acknowledging the contribution of Krashen (1983) in his affective filter hypothesis, in which the author explains that a learner’s state of mind can have a positive or negative influence on learning. The author emphasizes that emotional factors can block the input of linguistic information, negatively influencing language learning or acquisition (cited in Kushkiev, 2019).

Kushkiev (2019) believes that the affective filter hypothesis coined by Krashen should be taken into account to recognize the importance of emotions in English language learning, recognizing that they play a preponderant role at the intrapersonal and interpersonal levels. English language learning usually emphasizes the use of the communicative method, which requires collaborative work, in which the participant recognizes his or her internal capabilities and the ability to share knowledge with other members of the group (Kushkiev, 2019).

Overall, the findings in this study indicate that students can be rational and conscious beings in what they think. Also, they can recognize their strengths or weaknesses. In English language learning, it is vital when students recognize from their initiative that they need to be responsible and autonomous in their learning.

Likewise, it was found that the students have enough motivation to make decisions and execute actions that allow them to grow in learning English independently. They have the empathy that ensures they establish good relationships with their peers and the social skills to relate with others. In this sense, in learning English, it is essential to create learning networks among peers and other users of this language to exercise communication skills.

Finally, in the current context, UNAN-Managua has adopted the competency-based model, which has among its three elements the attitudinal dimension. For this reason, it was of great value to know the levels of emotional intelligence of the students to recognize the emotions that are manifested in the attitudes and behaviors of the individual. There is no doubt that the affective part is manifested through emotions and gives off a favorable or adverse predisposition to what happens inside and outside the ecosystem of learning a foreign language.

CONCLUSIONS

The described results show the positive relationship between emotional intelligence and students’ language learning outcomes. These findings mean that if we improve students’ emotional intelligence we can expect better results in their second language learning process, on the other hand, students with higher emotional intelligences can be more successful in their academic competencies and their individual lives.

Based on the results of this study, it can be stated that emotional intelligence affects English language learning. As the researcher found, emotional intelligence played an effective role in speaking ability. The findings have also shown that there is a significant correlation between emotional intelligence and reading and writing skills.

The relationship between second language learning and emotional competencies is not surprising given the nature of English classes in foreign language situations. Stress management, general mood, and adaptability are among the aspects that can greatly help language learners.

The findings of this study can serve as recommendations to instructors to modify methods that may be appropriate for students and their level of emotional intelligence and can also help them select appropriate teaching materials for students with different abilities. Accordingly, educators should be aware of their students’ emotional intelligences because when a teacher has a picture of his or her students’ strengths and weaknesses in different areas of intelligence, he or she can help them discover and develop their intellectual abilities.

In addition, English teachers are expected to be familiar with the concept, striving first to increase their emotional competencies and then to improve the emotional intelligence of their students. Materials developers should include techniques that pay more attention to emotional factors, leading learners to greater self-discovery and discovery of others.

WORK CITED

Abdolmanafi Rokni, SJ, et al. (2014). Investigando la relación entre inteligencia emocional y logro del lenguaje: un caso de TEFL y NO TELF en Estudiantes universitarios. IJLLALW - Revista internacional de aprendizaje de idiomas y lingüística aplicada , Volumen 5 (3), marzo de 2014; 117-127 ISSN (en línea): 2289-2737 e ISSN (impreso): 2289-3245.

Gardner, H. (1983). Estados de ánimo: la teoría de las inteligencias múltiples. . Nueva York: Básico Libros.

Goleman, D. (1998). Inteligencia Emocional . Nueva York: Kairós.

Gutiérrez, N. (2020). Inteligencia emocional percibida en estudiantes de educación superior: análisis de las diferencias en las distintas dimensiones. Actualidades en Psicología, 34(128), pp.17-33.

Hernández, R., Fernandez, C., & Baptista, P. (2014). Metodología de la investigación. México: McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

Kushkiev, P. (2019). The role of positive emotions in second language acquisition: some critical considerations. Mextsol Journal, , 43(4), pp.1-10.

Mayer, J., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. (2000). Modelos de inteligencia emocional. Sternberg, R. Manual de Inteligencia , Cambridge, Reino Unido. University Press.

Méndez, M. (2022). ). Emotions experienced by secondary school students in English classes in México. . Colombian Applied Linguistic Journal, , 24(2), pp.219-233.

Ocaña, J. (2011). Mapas mentales y estilos de aprendizaje. México: Editorial Club Universitario.

Pishghadam, R. (2009). Un análisis cuantitativo de la relación entre Inteligencia Emocional y el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras. . FLT, Revista Electrónica de Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras / Universidad Ferdowsi de Mashhad, Irán, vol. 6 No. 1 pags. 31-41.

Ramírez, E., Espinoza, M., Esquivel, I., & Naranjo, M. (2020). Inteligencia emocional, competencias y desempeño del docente universitario: Aplicando la técnica de mínimos cuadrados parciales SEM PLS. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, ., 23(3), 99-114.

Roa-Rocha, J. (2022). Competencias lingüísticas previas de inglés en estudiantes de primer año FAREM - Matagalpa, UNAM-Managua. Nicaragua. Revista Científica de FAREM-eSTELÍ,, II 43, 61-78 https://doi.org/10.5377/farem.v11i43.15139.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. . Emotion, disclosure, and health, 125-154.

Stake, R. (2005). Investigación con estudio de casos. Madrid: Ediciones Morata.

Vigotsky, L. (1979). El desarrollo de procesos psicológicos superiores. Barcelona: Crítica.

Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: design and methods. London: Sage Publication, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Zarafshan, M., & Ardeshiri, M. (2012). La relación entre la Inteligencia Emocional, estrategias de aprendizaje de idiomas y dominio del inglés entre estudiantes universitarios iraníes. EFL, www.wjeis.org/FileUpload/ds217232/File/11.zarafshan.pdf.

Zarezadeh, T. (2013). El efecto de la inteligencia emocional en el aprendizaje del idioma inglés . Procedia - Ciencias Sociales y del Comportamiento, 84 (2013) 1286 – 1289 .