ISSN 2410-5708 / e-ISSN 2313-7215

Year 13 | No. 37 | June - September 2024

© Copyright (2024). National Autonomous University of Nicaragua, Managua.

This document is under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International licence.

Ecological transition, everyday knowledge and humanization of learning: a transformed school

https://doi.org/10.5377/rtu.v13i37.18129

Submitted on November 03rd, 2023 / Accepted on May 23rd, 2024

Juan José Cuervo Zapata

Bachelor in Physical Education and Sport, Master in Educational Sciences and Doctoral Student in Educational Sciences, Universidad de San Buenaventura

Professor Faculty of Education, Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia.

Dora Inés Arroyave Giraldo

Research professor at the Faculty of Education, Universidad de San Buenaventura-Medellín, Colombia.

Section:Education

Scientific research article

Keywords: solidarity learning; school; technological mediation; humanizing practices

Abstract

The post-pandemic school needs to be installed in other social views, allowing the construction of collaborative networks between parents, students, teachers, principals, and other staff within the institution, as well as companies and the surrounding context. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to analyze the role of the school in welcoming diversity and in the rescue of transformative potentialities; given that when education is considered as a practice open to cultural diversity and human relations, it allows and hosts empowerment, emancipation, and creation as transforming elements of life itself, since they provide the entrance to knowledge and relational learning. Hence, the teacher is a co-creating agent, when he/she allows the learners to be linked to the process, to question what has been taught, and where uncertainty, astonishment, creativity, confrontation, and initiative are valued as possible ways for learning.

Introduction

“Difficult times call for encounter, vindication and hope. Hence, today the need for a school as a scenario of vital encounter is clearer, sharper and more frequent” (Vargas and Hernández, 2023, p. 79).

Classroom teaching from organic thinking installed from the ecology of knowledge tends to be multidirectional since actors intervene in a space that allows the flow of experiences, and when these are listened to, discussed, and staged; it allows learning to be more meaningful, because it is nurtured at every moment when the natural and social reality in which the person is living is put in evidence. Therefore, this review text presents three views or clues to re-signify teaching practices; the first view reflects on the ecological transition in the school as a welcome to diversity, where an approach to organic thinking is approached as an invitation to create with nature and solidarity learning is assumed to work hand in hand with sustainable development.

A second view explores the relevance of returning to everyday knowledge as a pedagogical alternative in teacher training, given that research should be merged in the educational system with the previous knowledge of each student, since it allows the teacher to think of other ways-feelings-actions to carry out teaching, since, by participating in a constant literacy and inquiry in their training, it makes alternatives emerge from them to address the content, transform it and articulate it along with their pedagogical work.

Finally, the third view contemplates the post-pandemic school as a new scenario for the humanization of learning in the digital era, because when it is said that education requires experiencing both the formal and real planes, it implies that the discourses used in the classroom are transferred to experiences or valuation of everyday knowledge that students have, due to the fact of being in a world of life that is fluctuating, diverse and advances rapidly in terms of technological mediation.

Development

Ecological transition in the school as a welcoming of diversity

“We are filled with admiration for the diversity of cultures, of human habits, of ways of giving meaning to the world. We begin to welcome and value differences” (Boff, 2011, p. 25).

Education needs to move towards other formative possibilities that contemplate understanding, care, and contact with nature; where all participants of the educational community can feel, dialogue, and therefore have new connections from an organic thinking, that is, based on direct experience and interaction with the natural environment. In addition, from an own recognition as a human being that enhances the dialogue with the diverse, with the conflicts present in everyday life and with those established structures such as the curriculum; where the latter, as mentioned by Rocio & Arroyave (2021):

Thought as an organizational axis of education seeks to generate contextualized proposals, provokes the rethinking of the school in the richness of the experiences granted by the experiences of the students and their contexts, and is strengthened in the vision of the cosmopolitan teacher who is in constant reflection of his practice. (p. 98).

Making an analogy of Mother Earth and the formation of a student, as it is presented in the new paradigm of the planetary community where not only an interest in the use of natural resources predominates, but also an open invitation to the protection of nature, to listen to its heartbeats, voids and cracks; the student does not only need an operative preparation of theoretical mastery of a particular knowledge, since the priority must be the acceptance of an adventure for learning, the articulation of knowledge with its sensibility, the peaceful coexistence, the understanding of inhabiting a space that is transformed to the extent that it is shared and constantly intervenes with others. Because of the construction of knowledge:

It is also done in the dialogue and appropriation of other forms of access to nature. All the versions that cultures have given of their way through the world can help us to know more and to better preserve ourselves and our habitat. Thus arises the sense of complementarity and the renunciation of the monopoly of the modern way of deciphering the world around us. (Boff, 2011, p. 24).

Organic thinking is an invitation to create with nature.

Returning to the logic of complementarity and dialogue, organic thinking allows the actors to express, feel, and communicate their ideas, experiences, emotions, and concerns at any time, since from these spaces it is possible to build or reflect on a particular topic of interest that allows the teacher to cross-cut their knowledge with another area, thus ensuring a more holistic understanding of the various routes of attention to a problem.

It is time to think about the teaching and learning process from the pedagogy of the question, not to insist that students answer what we teachers want them to answer. It is time to start thinking about an education where students can create a multiplicity of questions based on the contents (Lázaro, 2022, p. 202).

Therefore, the student is a transformational agent due to his capacity to perceive, attend, and evolve the knowledge-oriented by the teacher. In this sense, it is vital to have a classroom organization where everyone can participate in their training and can collectively manage information from academic literature, dialogues with other people, and the natural (organic) environment, which implies an appropriation of their life. In this regard Boff, (2011) expresses that it is important to undertake actions of “greening everything we do and think, to reject closed concepts, to distrust unidirectional causalities, to propose to be inclusive against all exclusions, conjunctive against disjunctions, holistic against all reductionisms, complex against all simplifications” (p. 27).

Now, the ecology of knowledge allows all appreciations to be valued, even if they are distant from the thematic focus to be addressed since knowledge is woven from the discussions that increase the arguments from a more reflective and proactive stance, since “the ecology of knowledge seeks to provide an epistemological consistency for a proactive and pluralistic thinking” (Santos, 2009, p. 185). Therefore, it is important to place these discourses in a school environment to procure in daily practices socialization, invention, creativity, and active listening in the face of a problem or event that has occurred, since:

It is necessary to restructure the educational models, and to rethink from other epistemological bases following current needs, changes in educational models or curricula will be of no use if the way of thinking, acting, living, and coexisting is not innovated. It is necessary to work in the classroom respecting the diversity of thought, each human being is linked to his cultural traits, and consequently, multiple ways of thinking coexist (Estrada-García, 2023, p. 15).

Inclusively, it is relevant to review the contributions and difficulties of the periphery of the educational institution because it is part of the world of the learner’s life, and from this other training processes are generated:

Knowledge interacts, and intertwines, and, therefore, so does ignorance. Just as there is no unity of knowledge, there is no unity of ignorance. The forms of ignorance are as heterogeneous and interdependent as the forms of knowledge. Given this interdependence, learning certain forms of knowledge may imply forgetting others and, ultimately, becoming ignorant of them. (Santos, 2009, p. 185)

Certainly, “today there is much talk of a paradigm shift, of the passage from a more ideistic-mechanistic paradigm to a more vital-organic one” (King, 1998, p. 33), for this reason, organic thinking is developed to expand the relationship between students and their environment. In fact, by using it, the teacher enables the dialogue of knowledge and experiences that allow the construction of knowledge from a collective view where everyone contributes from their faculties, moreover, it includes dimensions that do not come directly from a curriculum such as the active and subjective, where “all knowledge is testimony since what they know as reality (its active dimension) is always reflected backward in what they reveal about the subject of this knowledge (its subjective dimension)” (Santos, 2009, p. 188).

Solidarity learning as a path to sustainable development

It is important to increase solidarity among students, since in times of crisis as was the pandemic of COVID -19; it was required to address situations that strongly affect social, personal, and family spheres, as well as access to education, and health, among others; because the concept of development has taken root from an update and excessive use of natural resources in society, anesthetizing humanitarian aid, likewise, it happens with globalization that “has led to a loss of economic autonomy of States” (Morin, 2020, p. 41).

In this sense, it is convenient to adopt a path for sustainable development in the school environment, since it is known that “it is currently important for education to focus on sustainable development since it is necessary to ensure a balance between economic growth, social equity and environmental preservation (Pizà-Mir et al., 2023, p. 14).

Thus, it is necessary to allow a gradual ecological transition in the students starting with small actions from the reflections and discourses of protection of nature in their immediate context, so that later the teacher in a transdisciplinary way begins to pose challenges that involve decision making, teamwork and complex thinking in the sense that it allows the opening of beliefs, roots and particular customs, to promote a more solidary education and thought in the preservation of the common home, since “hope lies in continuing to awaken minds and in seeking another way that the experience of the mega crisis will have stimulated” (Morin, 2020, p. 48).

Also, it is necessary to consolidate work networks in the school scenario, since doing so allows the entry to multiple and diversity of ideas and sensations that begin to outline other meanings and actions to rescue the potentiality of each person and not only a stagnation in objective results, institutional performances or individualized performance, since in education it is valuable to seek the harmony or balance between the two goods (cosmic and particular) since “all beings are interlinked because some need others to exist and co-evolve [...]” (Morin, 2020, p. 48).

But each one enjoys relative autonomy and possesses meaning and value in itself” (Boff, 2014, para. 3) and thus contributes to human and social development by tracing new paths towards a vision that understands the meaning of humanity and its dependence on nature.

The common good is not only human but of the whole community of life, planetary and cosmic. Everything that exists and lives deserves to exist, to live, and to coexist. The particular common good emerges from harmony with the dynamics of the universal common good. (Boff, 2014, par. 9).

Now, in this line of interconnection, we find the training of teachers, which is considered preponderant to link the contents and teaching methodologies from solidarity pedagogies, since these become alternatives that “not only promote social progress, but also improve the quality of education, formation of values and principles in those involved” (Perdomo-Guerrero et al., 2023, p. 93). In addition, because they conceive that students coexist in a world that is changing and requires a strengthening of teamwork, as a starting point to access sensitively to nature and social reality, for this reason, the teaching team must be convinced that

A plural horizon, open [e] tracks on a path to be built, in which problems such as social transformation, critical thinking, social ethics, contestation movements, and popular education, are reconstructed with a flavor and a sense of this time by old actors transformed, other new and some just in training (Mejía, 2019, as cited in Arroyave, 2023).

Hence, the main function of the teacher is to accompany or mediate the learning processes by bringing examples of the context in which the learner develops to make the other visible, additionally he/she has to propose a formative evaluation that includes dynamizing the activities, thinking about otherness, to reflect and propose actions applicable to personal and social life, because “getting involved in the educational experience encourages the companion and the accompanied to let themselves be touched by the experience, to observe and reflect on that reality, and in that dynamic to review their feelings” (Sanchez & Del Valle, 2022, p. 32). 32).

Another of the existing problems in the school context that prevents the consolidation of supportive learning as a way for sustainable development is that the different actors of the educational community do not question the established curriculum, nor do they allow the epistemic dialogic confrontation to verify if they respond or are required for the current dynamics, i.e. it is not propitiated within the framework of the curricular postulates of the educational institutions “that authentic epistemological dialogues between different knowledge are viable” (Hernández, 2023, p. 290). Given the above, “thinking of a collective as a formative construction becomes essential, and also implies thinking and talking about communication because it is also talking about ruptures, barriers, and these are seen as inhibitors of the processes of knowledge construction” (Lázaro, 2022, p. 207).

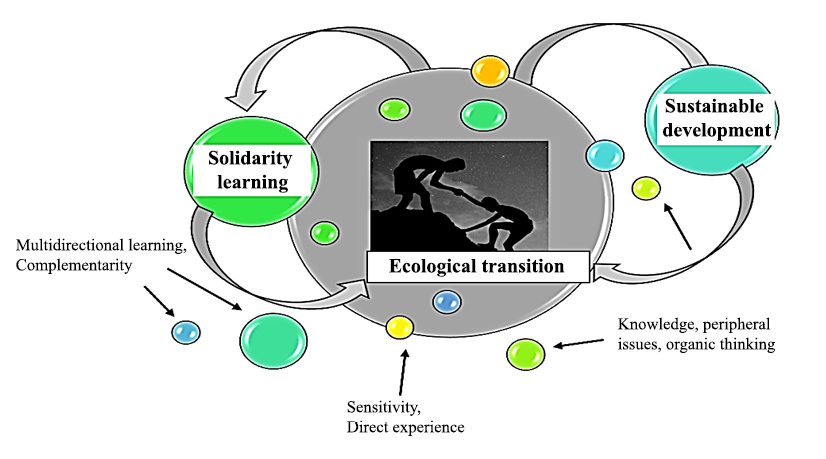

For this reason, undertaking sustainable development from a formative perspective requires an open system of multidirectional communication where the tasks to be performed allow a logic of complementarity (Boff, 2011), that is, there is a constant review among the participants (students-teacher-context) of personal experiences in contrast with the natural reality (see figure 1); since “feedback in the present contexts, sharing experiences among students, analyzing the contextual reality and socio-educational actions for social commitment are fundamental because they generate competence to improve sustainable development” (Pérez & Pérez, 2023, p. 13329).

Figure 1.

Ecological transition in the school as a welcome to diversity.

Source: Own elaboration

Return to everyday knowledge as a pedagogical alternative in teacher training.

The origins and trajectories of humanity unfold through diverse narratives. These narratives, which reflect the plurality of historical spaces and anthropological times, not only problematize the hegemonic versions of these origins and trajectories but also offer novel keys for a critical and renewing reading of the present (Rueda et al., 2022, p. 9).

Educational processes need to take up again conceptual and practical elements of popular education and social movements since these two provide space for reflections on critical thinking, the reading of daily realities, and the problems that are generated there while increasing interest in responding to collective needs that help in the recognition of the other, of the territory and human sensitivity; given that “social movements and popular education begin to outline the elements that will allow them to raise alternatives and new forms of thought and action, which try to overcome the exhaustion of critical thinking” (Mejía, 2019, p. 36).

Teacher mediation in the rescue of transformative potentialities.

Teacher training must transcend both in its methodological approach in the classroom (evaluation strategies, planning and monitoring of the academic process), as well as in the discourses it addresses with each participant because the training processes that occur in various school and informal contexts can be defined as:

Lattices that express a range of senses and meanings that show the imaginaries and self-representations generated by both trainers and students from the relationships they establish with themselves, with others, and with the context in which they interact. (Hernández et al., 2023, p. 2).

It is, therefore, an interrelation between knowledge/context that is a priority today because it grounds and gives meaning to teaching, takes up experiences, and builds knowledge that is permeated by narratives, gestures, art, symbols, images, encounters, movement and literature, each of these with particularity in common and that is that they have within them issues of introjection and projection of life itself. In this sense, the role of the teacher implies:

To be as patient as a watchmaker to reconstruct the interests of the subjects, today pluralized, to invent a new organizational capacity with other forms that speak to us of an expanding plurality, and to understand that diversity rather than a limitation is an enrichment. (Mejía, 2019, p. 66).

Hence the value of the teaching praxis is “to exercise a practice founded on the necessary openness to the other, a practice in which dialogue becomes an epistemological requirement for a socially committed experience and whose reflection, shared collectively, generates multiple authorships” (Freire, 2015, p. 35). In this sense, the important thing is to be aware that the rupture of those traditional structures makes these two actors embrace each other both in academic and human trajectories.

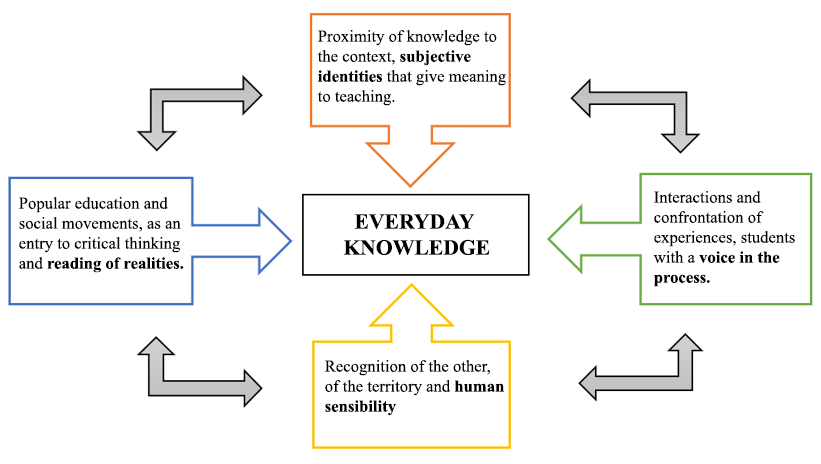

Thus, allowing the flow of daily knowledge within the pedagogical practices helps the entire educational community to think from the knowledge that is built and deconstructed from the interactions themselves and the confrontation of experiences, where each participant has a voice in the process and can account for its origin; thus valuing “the different ways of being and being in the world that define uniqueness to open multiple paths to the construction of identity, the development of autonomy and the deployment of creativity” (Rico & Salazar, 2023, p. 48). Likewise, it is imperative to keep in mind the subjective identities (Mejía, 2019), since these give rise to a broader vision of collectivity, that is, of simultaneous learning where issues that are of interest to all are taken up, such as the environment, the recovery - valuation of the ancestral and the opening to knowledge from multiple perspectives.

Education is simultaneously a theory of knowledge put into practice, a political act, and an aesthetic act. These three dimensions always go together, they are simultaneous moments of theory and practice, of art and politics. The act of knowing, at the same time that it creates and recreates objects, forms the students who are knowing.(Freire, 2015, p. 63).

Therefore, teachers in their permanent formative process acquire specific experiences and knowledge according to their interests, disciplinary field, or population they serve, however, when several colleagues meet in the function of planning or reflecting on project proposals with students, it makes them begin to give importance to complex thinking that is dialogic. As narrated by Iribarren et al, (2023) “the dialogue of the scene would account for a process of epistemic co-production that, without ceasing to recognize academic knowledge, recovers and values the knowledge, practices, and experiences of those who inhabit the territory” (p. 249), given that its dialogue is a process of epistemic co-production. 249), since its conceptual framework allows the construction of new learning possibilities, which are not limited to reproductive matters of knowledge, or memorization; on the contrary, it enables the confrontation and implementation of activities permeated by the vital-organic context of each subject-student.

The reinvention of the school as an expansion of life.

The school needs in its usual dynamics, adjustments thought in terms of equity of conditions and opportunities for all students, the reinvention in its methodological ways of seeing the content as knowledge and a possibility of openness to change, of analysis concerning the social context in which the student develops; Indeed, in education “a re-formative system is required that not only imparts academic knowledge but also trains, educates to live together in values and social cohesion, since this set is the one that over time can generate changes” (Espinosa & Restrepo, 2023, p. 44), aspects that in any case can generate changes” (Espinosa & Restrepo, 2023, p. 44), aspects that if they are not taken into account in the plural pedagogical practices, would only remain a theoretical concept that is difficult to include in life itself without a previous mediation of learning.

At this point, it is where the teacher becomes relevant, because he/she is the subject who mediates, creates, recreates, and expands the possible routes of solution to a problem to enter into a deep work of exploration-research; since the notion of expansion refers to various “ways of educating. If the form is changed, most of the components are altered: time, spaces, subjectivities, and, above all, speed. With this, teaching, learning, and the role of knowledge are transformed” (Martínez-Boom, 2019, p. 317).

Furthermore, Martínez-Boom, (2019) expresses that learning is a fundamental component to keep in mind in discussions and reflections in every pedagogical scenario, because:

A society devoted to lifelong learning demands from educational research an epistemological commitment capable of legitimizing and deepening the positive aspects of this narrative, i.e., extolling self-learning, emphasizing the need to learn, valuing the richness of lifelong learning, expanding the effects of collaborative learning and betting boldly on active learning. (p. 332).

In the same way, evaluation should be constituted more than an element of measurement, performance in a constant, critical, and reflective process in attention to all the actors involved in learning, i.e., it is the harmonization between knowledge, encounter, and communication of what is created or experienced. In this regard, Sánchez and Solís, (2023) mention that from a formative evaluation, “learning can be contrasted and reflective feedback can be given; they also help teachers to discover the strengths and weaknesses of their own pedagogical practice” (p. 201).

Thus, the formative aspect occurs when the subject recognizes his potentiality and that of the other in a space that implies a dialogue of knowledge since the teacher’s exercise “should be based on the construction of an ideal subject, dedicated to the social task of educating others according to the designs of a particular culture and context without ignoring his participation in the world” (Montoya & Arroyave, 2021, p. 56) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Return to everyday knowledge

Source: Own elaboration.

The post-pandemic school: a new scenario for the humanization of learning in the digital age

In the encounter we see the living classroom, the classroom as a scenario for the cultivation of life, the classroom as a place that calls for testing, disruption, and exploration as a possibility of originating the birth of the new, rather than the repetition and reproduction of preconceived models. (Uribe, 2023).

Within the framework of school scenarios, it is essential to review the curricular reforms that have taken place to optimize learning, to promote the recognition of the problems that arise from the interaction between the actors of knowledge such as students-teachers and contexts, helping in “the understanding of the plurality of the classroom, the importance of mobilizing contextualized and meaningful learning, which favors participation, cooperation and democracy in classroom environments” (Restrepo & Restrepo, 2022, p. 63).

Likewise, it allows early actions to be undertaken from the teaching role to review at the content level its applicability to the environment, its articulation to inclusion and diversity policies, and its approach to the transformation of knowledge, allowing the voice of students in the classroom practices and outside the classroom (Vigo-Arrazola et al..., 2023), as well as to “guide the redesign of the curriculum to meet, along with the demands of the new context linked to the economy, those others that concern the individual and his or her integration into society” (López, 2020, p. 149). It is necessary, therefore, that each student can explore, redesign, and enhance their cognitive, social, motor, and emotional capacities to adapt to the current contingencies that are linked to the educational system; to the extent that they are built in the context of the new context, it is necessary that each student can explore, redesign and enhance their cognitive, social, motor and emotional capacities that allow them to adapt to the current contingencies that are linked to the educational system.

Learning experiences capture the student’s interest in learning, framing the use of technology in a new pedagogical model that seeks to develop autonomy in learning and in the use of time, and focuses on the development of competencies and socioemotional skills. (Arias et al., 2021, p. 16).

On the other hand, in the teacher training process, reflecting on the curriculum that is given or previously designed provides the basis for the achieved or situated curriculum, the latter being the one that allows the learning process to develop in a bidirectional, flexible, dynamic, complex and differential way; since it allows other views, knowledge and ways of approaching a specific case or situation resulting from human relations, but especially, it fulfills the purpose of “providing students with the necessary tools such as class activities, individual or group tasks that allow critical reflection, creative learning and above all that there is effective communication” (Arias Rentería & Ibargüen Maturana, 2023, p. 9358).

Human complementarity and technological mediation in education: A perspective for the 21st century.

One of the lessons that confined education left us consists in the idea that to avoid fragmented knowledge, it is urgent to return from teaching strategies to books accompanied by digital tools that allow the search, analysis, connection, or recovery of information learned in other cycles, and the understanding of the topics from a complementary deepening to the one offered by the teacher. As López (2020) mentions:

Adaptability [...] will require judicious adaptations of what is taught and how it is taught. But adaptability also affects the demands of the immediate context, specific to each country, and implies the application of the principle of progressivity, that is, of reforming gradualism as a method that ensures progress and, at the same time, guarantees its consistency. (p. 152).

Another lesson refers to the family and how important it is to recover parental involvement in the formative process of all students since it is beyond doubt that “The family and the school are the closest and most appropriate environments for the development of the human being, these should be open, supportive and mutually flexible” (Aguirre, 2022, pp. 28-29), in that sense, it is expected that the various communicative acts are in tune with the learning outcomes that are intended to be achieved.

On the other hand, the pandemic evidenced the lack of connectivity, equalization of opportunities to access knowledge, and the lack of population characterization in the different territories, which led to a lack of knowledge or little adaptation of the educational system to community needs. It also reflected the lack of a complementary relationship between the educational actors as a possibility to provide counseling and experiences to the specific group. It can be said then that the health contingency highlighted the role of the teacher to recover those complementary relationships both in the human team and in the search for support or resources that make possible other alternatives to approach knowledge, such as from the hybrid that mixes experiential activities with reflective supports from technological mediation. In other words

The pandemic, with the increase in demand, facilitated a new discussion on educational dynamics and contributed to conceive the complementarity and a necessary balance between various components, such as face-to-face, virtual, synchronous and asynchronous, theory and practice, learning and social life, which puts the look more closely to models that would allow combining, for each content or professional field, the best of the diversity of such dichotomies referred to (Rama, 2021, p. 70).

In this context, it should be considered that hybrid education allows complementing the curriculum established in the school in its elements of flexibility and adaptation of learning as a response to learning styles since it bets on problematizing the needs of both actors (teachers-students) in the search for a balance between conceptual or academic understanding and the environment, because “hybrid models allow the ability of students to learn at their own pace and to achieve self-directed learning, key skills that must be developed to stimulate learning” (Arias et al.., 2021, p. 21). In turn, Rama (2021) states that,

Hybrid education implies the construction of new education, differentiated forms of management with the use of synchronous, asynchronous, automated, and manual forms; more flexible dynamics to meet the growing demand for access and promote the creation of a diversity of learning environments adjusted to the singularities of the various professional, knowledge and social fields, and to take advantage of the breadth and diversity of virtual forms of development (p. 121). (p. 121).

In addition to the above, it can be said that technological mediation allows the creation of support networks in the training process, on the one hand, it is reflected in the teacher when he/she can articulate synchronous and asynchronous tools to enrich their classes or deepen their programmatic content, in addition, it allows monitoring and evaluation of the process of each student to discuss the knowledge learned with reality. On the other hand, it is evident in the students when they resort to other ways of graphing, visualizing, analyzing, and understanding a specific topic with the support of easily accessible digital resources, while they can observe and give feedback on the other proposals of their fellow students.

The post-pandemic school: Towards humanizing pedagogical practices

It is urgent to assume the challenges that arose from the contingency that was unexpected for all citizens of the world, as is the case of resignifying pedagogical practices focused on situational-ecological actions that prevail human development rather than the mere transmission of knowledge; in other words, “Humanistic training for the XXI century requires a change of mentality in many aspects of our educational reality” (Nasarre, 2022, p. 25), as an example, there is a dialogic relationship, i.e. the establishment of closer dialogues, in a bidirectional way between students and teachers. 25), as an example we find the dialogic relationship, that is, the establishment of closer dialogues, in a bidirectional way between students and teachers (Uribe, 2023), since it is important to recover the channels of trust and communication to address the problems of mental health and emotional education, from this perspective, “post-pandemic educational, pedagogical and didactic management is demanded, as a process of an educational system, [which] should start from today, from the reflections of the sense it will have ‘in the school to come’, a rethought, reconfigured school” (Arroyave, 2021, p. 20).

In line with the above, it should be noted that the teacher’s ability to prepare for cognitive and metacognitive challenges to guide learning is fundamental, since it influences the organization of the learning environment to respond to the needs and interests of the students, since “the teacher is not a disseminator of content. He must design an exciting learning experience that transcends the thematic aspects. In addition, he/she must be a good mentor, empathetic to the student’s needs” (Pardo, 2023, p. 21). Therefore, an environment designed for social reflection makes both actors in the process assume within themselves a desire and motivation for the transformation of their lives and environment. As Arroyave (2021) expresses,

It is necessary to move towards a school where interpersonal and intergroup relations are privileged over the fulfillment of prefixed, stereotyped, and homogenizing roles; to move towards school environments where open communication is generated among the different educational actors, added to the creation of multicultural school environments, as a value of cultural diversity. (p. 22).

In this way, pedagogical practices, when assumed from a cooperative, critical, and humanizing perspective, make the programmatic contents, class methodology, didactics and space setting converge towards more inclusive bets in terms of accepting and enhancing diversity as an essential foundation in the collective construction of knowledge, because in short, “it implies a scenario for self-learning and continuous improvement, so it is a constituent element of lifelong learning and professional development” (Montoya & Arroyave, 2023, p. 13).

It also helps the evaluation processes to be assumed as progressive sequences or intentional processes whose purpose is to show the routes to understand the knowledge, given that

If very specific and formalized content is not presented about what the student knows and can attribute some meaning to it, it only serves to create increasingly insurmountable barriers between personal knowledge, school content, and academic knowledge that gradually approach the so-called school scientific knowledge (Arroyave, 2021, p. 31). (Arroyave, 2021, p. 31).

Similarly, critical thinking is assumed as a key component in the school scenario to the extent that it makes the participant perform an introspection of his or her life to act from an ethical and collective position, which, as stated by Sánchez-Pérez and Gómez (2021), critical thinking “is a capacity that can be trained with the intention of improving the way of being and being in the world. The interest and curiosity generated from the educational experience must have an intentional character” (p. 117). In other words, this is generated when pedagogical practices are intentional and give room for the student’s protagonism to propose and alter the structure prefixed by a curricular grid since his experience enters the scene for the construction of knowledge.

Now, from the teaching role, it is evident the need to rethink the pedagogical practices to know how critical thinking is being applied: as a means to analyze information and make a judgment, or as an understanding at the level of social reality, given,

In our context, it is not critic the who most limits the possibilities of development, of action in digital environments, of interaction with others, of discovering one’s own identity, but the one who interprets them under eminently formative criteria examines them, modulates them and responsibly configures them by educational objectives, who is more critical (Sánchez-Pérez & Gómez, 2021, p. 122).

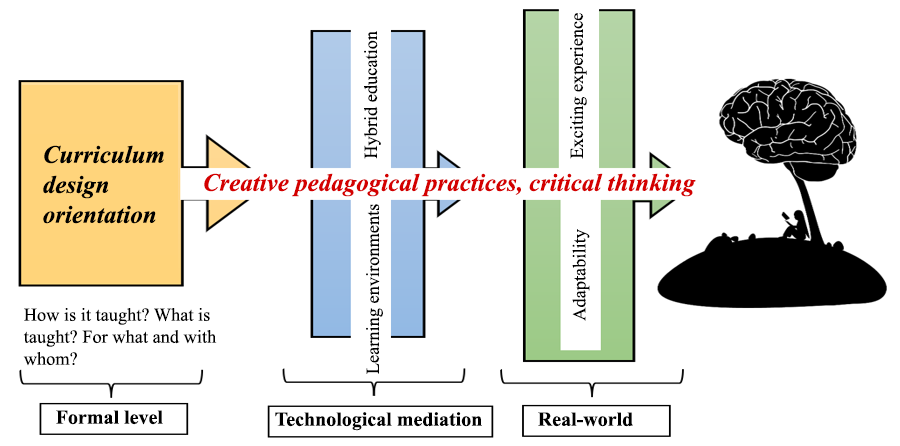

Finally, by way of recapitulation, it is convenient to keep in mind that, to successfully implement hybrid models in teaching and learning processes, four pillars are required: new pedagogies and teaching profile, equipment and connectivity, platforms and content; and student monitoring and evaluation (Arias et al., 2021). In any case, a complementary transformation in its components that allows responding to the challenges of education in the 21st century (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Orientation of curriculum design towards creative and hybrid pedagogical practices.

Source: Own elaboration.

Conclusions

In the educational context, alternative ways should be contemplated at the curricular level, since the subjects who are in a constant process of co-learning (student and teacher), are in direct contact with experiences and interactions with the natural environment; therefore, it is necessary to rethink the school from the cultural richness and organic thinking; because in that sense, the flourishing of sensitivity, the dialogue with nature and solidarity learning, essential aspects for the improvement of coexistence and the preservation of the habitat, is embraced.

The above implies that the role of the teacher within the educational scenario and with projection to the periphery includes in its pedagogical practice the interrelational learning that makes it possible to anchor the dimensions of subjectivity, sensitivity, and sensory encounter so that the student feels accompanied and recognized and, in that sense, can think of himself as a reflective actor and builder of his life project.

Finally, the pandemic highlighted the relevance of diversifying resources, strategies, and methodologies inside and outside the classroom to appreciate the diversity of students in their initiatives and, above all, from the voices of their daily lives. Likewise, regarding the co-construction of knowledge, the contingency revealed that the center of this does not lie in a rigid structure or intervention without mediation of the other, on the contrary, it is assumed as valid, as it considers the experiences, beliefs, and previous knowledge as a starting point, in contrast to the given, the pre-established and predetermined offered from a positivist epistemology.

Works Cited

Aguirre Burneo María Elvira (2022). Factores contextuales de familia y escuela. En Aguirre et al., (eds.). Familia y escuela. Una visión desde la educación para la paz. Dykinson, pp. 23-50

Arias Ortiz, E., Dueñas, X., Elacqua, G., Giambruno, C., Mateo-Berganza Díaz, M. M., & Pérez Alfaro, M. (2021). Hacia una educación 4.0: 10 módulos para la implementación de modelos híbridos. https://doi.org/10.18235/0003703

Arias Rentería, Y., & Ibargüen Maturana, J. (2023). Reflexión crítica - constructiva entorno al currículo en Colombia, tendencias y metodologías activas. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(2), 9348–9365. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v7i2.6038

Arroyave Giraldo, D. I. (2021). Roles, prácticas, dinámicas de la gestión educativa, pedagógica y didáctica en tiempos de cambio. In Estudios multirreferenciales sobre educación y currículo: reflexiones en tiempos de pandemia (pp. 18–43). Bonaventuriana.

Arroyave Giraldo, D. I. (2023). Guía Seminario de línea de investigación: Estudios críticos sobre educación y currículo. Doctorado en ciencias de la educación. [Documento de apoyo con fines didácticos exclusivamente de circulación interna]. Universidad de San Buenaventura.

Boff, L. (2011). Ecología: grito de la tierra, grito de los pobres. Trotta.

Boff, L. (2014). Características del nuevo paradigma emergente. Koinonia.Org. https://www.servicioskoinonia.org/boff/arti culo.php?num=676

Espinosa Ortega, A., & Restrepo Valencia, M. (2023). Construcción de paz y memoria histórica desde la escuela: un recorrido histórico. Zona Próxima, 38, 37–65. https://doi.org/10.14482/zp.38.326.951

Estrada-García, A. (2023). Las Epistemologías del Sur para una educación emancipadora. Revista Portuguesa de Educação, 36(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.21814/rpe.23880

Freire, P. (2015). Pedagogía de los sueños posibles. Por qué docentes y alumnos necesitan reinventarse en cada momento de la historia. Siglo Veintiuno.

Hernández Córdoba, Ángela. (2023). Una mirada intercultural a la identidad y la subjetivación. Estudio con universitarios indígenas y urbanos. Ed. Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Hernández Aragón, M., Libreros Galicia, E. D., & Ocampo Tallavas, M. I. (2023). La formación docente desde las expresiones autoetnográficas de los formadores normalistas. Praxis Educativa, 27(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.19137/praxiseducativa-2023-270107

Iribarren, L., Guerrero Tamayo, K., Garelli, F., & Dumrauf, A. (2023). ¿Qué nos cuenta Pachamama? Una experiencia de diálogo de saberes, vivires y formación docente descolonizadora en educación ambiental. Técné, Episteme y Didaxis:TED, 53, 239–255. https://revistas.pedagogica.edu.co/index.php/TED/article/view/14919/12378

King Herbert (1998). King Nº 4: El Vivir y Pensar Orgánico. Nueva Patris

Lázaro, F. D. (2022). La formación docente: entre recetas y distopías. Revista Argentina de Investigación Educativa, 2(3), 201–220. https://acortar.link/dSYGkg

López Rupérez, F. (2020). Las reformas curriculares para el siglo XXI. In El currículo y la educación en el siglo XXI. La preparación del futuro y el enfoque por competencias (pp. 147–160). Narcea.

Martínez-Boom, A. (2019). ¿Para qué nos educamos hoy? Escolarización y educapital. In Genealogías de la pedagogía (pp. 273–304). Universidad Pedagógica Nacional.

Mejía, M. R. (2019). Reinventar la transformación social y Los nuevos desafíos de la educación popular y los movimientos sociales. In Acción social colectiva y pedagogía (pp. 35–94). En Acción social colectiva y pedagógica. Universidad Oberta de Cataluya.

Montoya Grisales, N. E., & Arroyave Giraldo, D. I. (2021). Conocimiento didáctico del contenido. Una revisión sistemática exploratoria. Revista Boletín Redipe, 10(8), 55–71. https://doi.org/10.36260/rbr.v10i8.1384

Montoya Grisales, N. E., & Arroyave Giraldo, D. I. (2023). La práctica pedagógica como fundamento de ser maestro. Actualidades Pedagógicas, 79, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.19052/ap.vol1.iss79.4

Morin, E. (2020). Los desafíos del poscoronavirus. En Cambiemos de vía, lecciones de la pandemia. Planeta.

Nasarre Goicoechea, Eugenio (2022). Por una educación humanista. Un desafío contemporáneo. Narcea Ediciones

Pardo Kuklinski, H. (2023). Los futuros inevitables de la universidad. Ideas para gestores hacia la consolidación híbrida. Editorial Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. https://acortar.link/SaIR2Q

Perdomo-Guerrero, C., Rodríguez-Villasmil, B., & Pirela-Hernández, A. (2023). Pedagogías de la solidaridad: modelo de aprendizaje servicio para la transformación social. Una visión desde la universidad. Cátedra, 6(1), 92–109. https://doi.org/10.29166/catedra.v6i1.4015

Pérez Velásquez, L. B., & Pérez Velásquez, S. S. (2023). Metodologías inclusivas para el desarrollo sostenible. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6(6), 13309–13333. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i6.4331

Pizà-Mir Bartolomé; Fernández Fernández Juan Gabriel; Cortès Ferrer María Magdalena; García Taibo Olalla y Baena Morales Salvador (2023). Currículum, didáctica y los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible (ODS). Reflexiones, experiencias y miradas. Dykinson

Rama, C. (2021). La nueva educación híbrida. En Cuadernos de Universidades. https://acortar.link/1sJD5R

Restrepo Quijano, A. M., & Restrepo Maya, W. A. (2022). Una escuela para entretejer juntos la diversidad y la inclusión. Revista Reflexiones y Saberes, 17, 51–64. https://acortar.link/KIaGx1

Rico, M. C., & Salazar Jiménez, J. G. (2023). Prácticas y saberes pedagógicos de las madres comunitarias rurales del municipio de Paya (Colombia). Acción y Reflexión Educativa, 48, 36–54. https://acortar.link/VC4Lmp

Rocio Pico, H., & Arroyave Giraldo, D. I. (2021). Educación como proceso dialógico donde el sujeto es el principal agente de cambio. Miradas, 16(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.22517/25393812.24863

Rueda, E. A., Larrea, A. M., Castro, A., Bonilla, Ó., Rueda, N., & Guzmán, C. (2022). Retornar Al Origen: Narrativas Ancestrales Sobre Humanidad, Tiempo y Mundo. Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales. CLACSO. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2v88dwj

Sánchez Flores, J., & Solís Trujillo, B. P. (2023). La evaluación formativa: un proceso reflexivo y sistemático de la práctica docente. Revista Conrado, 19(90), 196–202. https://conrado.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/conrado/article/view/2883/2789

Sánchez Reyes, M. T., & Del Valle Cermeño Guaina, D. (2022). Servir solidariamente, un rasgo esencial del aprendizaje para el desarrollo sostenible desde el compromiso social. DIDAC, 79, 29–38. https://acortar.link/EQ6eNh

Sánchez-Pérez, Y., & Gómez Calcerrada, J. L. (2021). ¿Es necesario un pensamiento crítico para la era digital? In González M.; Zaldivar J. y Olmeda G. (eds). Condiciones del pensamiento crítico en el contexto educativo del inicio del siglo XXI (pp. 115–126). Fahren House.

Santos, B. de S. (2009). Una epistemología del Sur: la reinvención del conocimiento y la emancipación social. Clacso. Siglo Veintiuno.

Uribe Pareja, I. D. (2023). estÉtica de los placeres: entre cuerpo y educación física. Una pedagogía vitalista. Editorial Kinesis.

Vargas Hernández Marco Fidel y Hernández Pino Yoli Marcela (2023). La escuela rural: encuentro ecosistémico y diálogo ecológico. En: Acosta y Rodríguez (Ed). Ecoliderazgo y educación rural. Universidad de la Salle, pp. 77-96

Vigo-Arrazola, B., Dieste, B., Blasco-Serrano, A. C., & Lasheras-Lalana, P. (2023). Oportunidades de inclusión en escuelas con alta diversidad cultural. Un estudio etnográfico. Revista Española de Sociología, 32(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.22325/fes/res.2023