ISSN 2410-5708 / e-ISSN 2313-7215

Year 8 | No. 21 | p. 103 - p. 122 | February - May 2019

© Copyright (2019). National Autonomous University of Nicaragua, Managua.

This document is under a Creative Commons

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International licence.

An approach to the rock art in four municipalities of the RACCN, Nicaragua

https://doi.org/10.5377/torreon.v8i21.8852

Submitted on October 15th, 2019 / Accepted on November 06th, 2019

Archeologist Kevin González Hodgson

Master in Scientific Research Methods

Professor-Researcher of the Archaeological Center of Documentation and Research (CADI)

UNAN-Managua, Faculty of Humanities and Legal Sciences

hodgsonk27@hotmail.com / chorotega310885@gmail.com

Keywords: rock art, interpretative approach, everyday life, iconography, pictograph, Autonomous Region of the North Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua.

Abstract

This research presents a stylistic classification of 45 graphic representations (petroglyphs and pictographs) of four municipalities of the Autonomous Region of the North Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua, the result of several stages of research. The main objective of this study was to analyze the rock motifs through an iconographic analysis that, also; involved determining the historical-cultural context of elaboration and the approximate meaning of the iconic characteristics identified in the selected specimens. According to the results from the iconographic description and taking into account important variables in its configuration, such as the elaboration techniques and the characteristics of the rocks on which the representations were expressed are substantial indicators to say that the specimens studied were elaborated on the basis of various degrees of technical and stylistic specificity, therefore, the cultural group that gave rise to this type of rock graphic manifestation left testimony of complex writings that allowed through images to represent their reality, that is, their daily life and environment with a very important symbolic framework.

Background

The present study is the result of several stages of research, which in principle arises from my undergraduate thesis called “Archeology in the RAAN: an approach to the past”, presented at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua in 2009. Since then, by several years together with another colleague, I have published another article1 on which data is collected and presented on this occasion. For this study, the main objective was to analyze the rock motifs through an iconographic analysis that, besides, involved determining the historical-cultural context of elaboration and the approximate meaning of the iconic characteristics described.

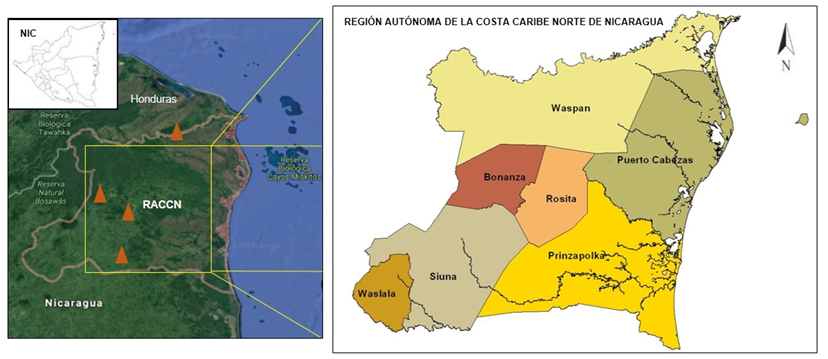

The sample-set comes from four municipalities of the Autonomous Region of the North Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua, specifically in the territories of Kirwas2, San Alberto3, Santa Fe and San Jerónimo on the banks of the Coco River corresponding to the municipality of Waspán, border area with the neighboring country of Honduras; Tungla and Buena Vista in the municipality of Prinzapolka, the community of Panama in the mining municipality of Bonanza and La Florida in the municipality of Rosita, territories inhabited ancestral by Miskitos and Mayangnas.

Scheme of the location of the places where the study sample comes from. Source: googlearth / adapted by the author.

With regard to the petroglyphs located in the municipalities of Rosita and Bonanza, they correspond to archaeological sites with rugged relief; on the other hand, the sample from the towns of Waspán and Prinzapolka4 are located in riverside areas, that is, among the streams in this case by the longest river in Central America, the Coco, and on the other hand by the Prinzapolka river another important river in the region of the Nicaraguan Caribbean.

By now, the ancient history of the North Caribbean Coast of the country is very little known, which has led to it being subject to much speculation as to its archaeological wealth; in fact, there are few historians and archaeologists who, interested in the past of our country, have directed their intellectual efforts towards this vast multicultural and multilingual region for several reasons since the lack of studies or related literature, economics or the climatic conditions that they hinder access to sites of archeological interest, therefore, the inhabitants of these regions have long been relegated to the historical study of their pre-Hispanic roots. Until recently, before the last century, the only information from this area consisted of research of some brief and descriptive reports, in addition to local fans who reported on the existence of ceramic sherds on surface and stone engravings.

In this regard, delving into the little literature at hand are some ethnohistoric and archaeological studies that account for the past in the North Caribbean, among which reported material evidence is reported, in addition to stone axes, mound structures and stone for grinding, “rock inscriptions, in different places on the Coco River such as Wirapani, Waspuk, Kirwas, above Raití, in Kumkum Mawan and in Tawit” (Conzemius, 2004, p.75). Similar context is the “Uli Was basin where petroglyphs have been observed that may well be about 2500 years old and thick dark brown ceramics, very tainted by use, which seems to have served for the preparation of meals at communal festivities likewise similar large vessels used for funeral burials” (Hurtado de Mendoza, 2000). Another referent of singular importance is the data offered in the book “Mayangna, notes on the history of the Sumus Indians in Central America” of (Houwald, 2003: 269), it provides clues about the identification of a type of pottery in the community of Santa Fe, Coco River determined as “Mokó Plain”5.

On the other hand and with few days of prospecting in 2007 and 2008, it was possible to verify that not only were some of the sites revealed by the researchers cited but also very unique material evidence of other types was found, that is, on that occasion the results obtained during two days of field allowed to document a total of 20 archaeological sites classified in relation to the type of evidence found among which stand out: sites with petroglyphs, with petroglyphs and surface material, with surface material and mound structures and caves, distributed in the municipalities of Waspán, Rosita, Prinzapolka and Bonanza (González Hodgson & Taylor, 2009, p.117)6, in addition, of the documentation and registration in the municipality of Rosita of 17 archaeological sites distributed between mound structures (2), surface material (12), petroglyphs (3) and statuette (1), as documented by the authors González Hodgson and Taylor, (2012).

Material and method

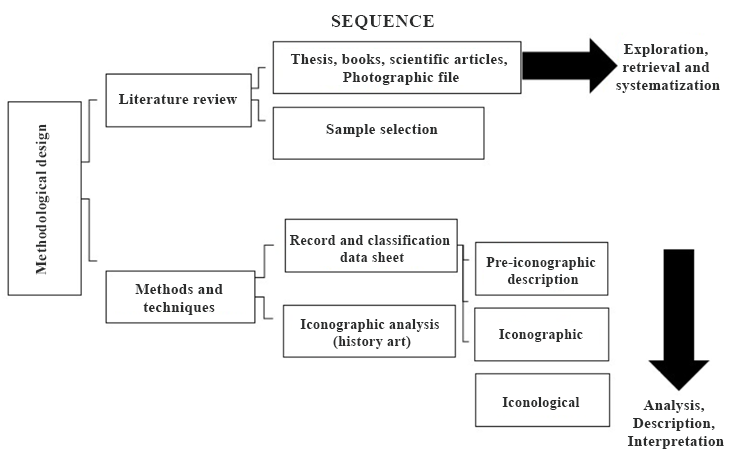

The procedure began with; 1) documentary search and selection of the 45 copies; the sample was selected from photographs taken directly at the sites as well as theses, reports, books and photographic archives provided by the TININISKA7 Cultural Center and local fans8 that allowed the redrawing process with the exception that they could not be established sequences from applied manufacturing techniques. 2) Elaboration of a technical record of each of the petroglyphs that allowed the initial characterization of the sample. 3) identification and classification of aesthetic features using iconographic analysis understood as the branch of art history that deals with the matter or significance of works of art as opposed to their form (Panofsky, 1979, p.45)9, taking account for three levels of interpretation: pre-iconographic or primary-natural significance of forms, iconographic or secondary significance-association of forms and the iconological level or intrinsic meaning of form content.

Synthesis of the procedure performed in the iconographic analysis process. Source: The Author

Description of the graphic representations

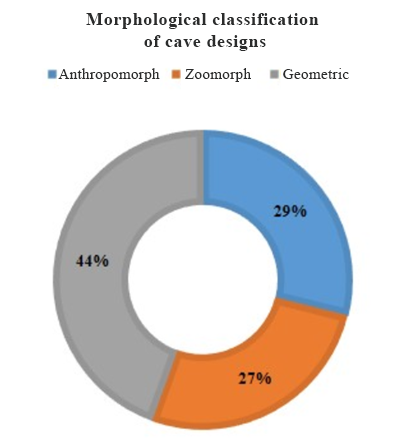

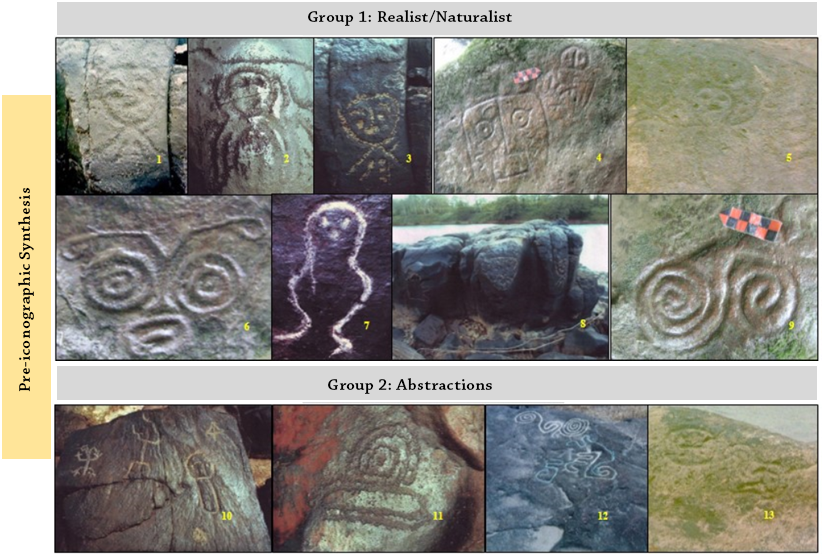

The results obtained allow us to differentiate roughly two types of rock manifestations including petrogravure (use of the carving technique) and pictographs or cave paintings (application of pigments on rocky surfaces); In the first level of classification or pre-iconographic analysis and according to the characteristics of the designs, two groups of visual elements were determined, the first one, abstract10 representations that belong mostly to geometric patterns (20), followed by elements anthropomorphic (13) and then zoomorphic representations with (12); Engravings with geometric characteristics are presented in a variety of designs such as double divergent spirals (43%) and spirals with more than three turns represent (52%).

Graph 1. Percentage of the rock manifestations identified by form. Source: The Author

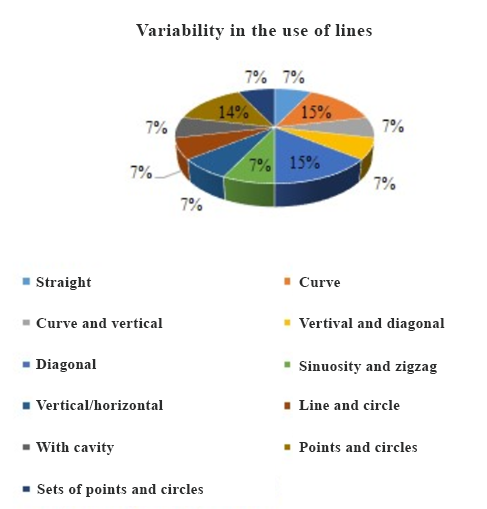

As for the variants identified in the use of lines, it stands out for the frequent use of the curve (15%) and the diagonal (15%), also, of points and circles (14%), followed by the use of straight lines. (7%), curve and vertical (7%), vertical or diagonal (7%), sinuosity or zigzag (7%), vertical and horizontal (7%), line and circle (7%), with a cavity (7% ) and set of points and circles (7%).

Graph 2. Frequency in the use of the lines technique in the designs. Source: The Author

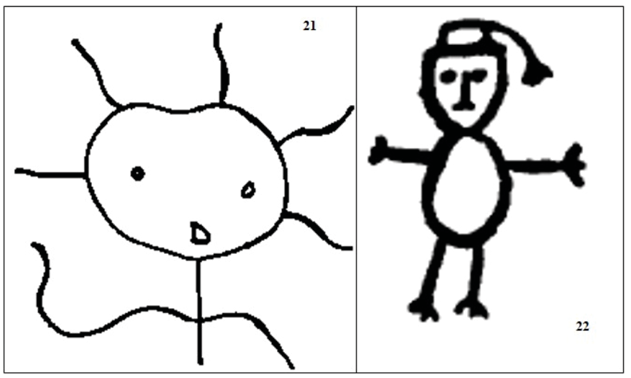

The data suggest that the geometric motifs have quite complex and imaginative features, at least this is shown by one of the specimens analyzed in this case defined as a soliform element eventually associated with astronomical representations either simply as a reflection signal of the star (sun) or, due to the fact of some more specific event such as eclipses and others linked to the suggested category.

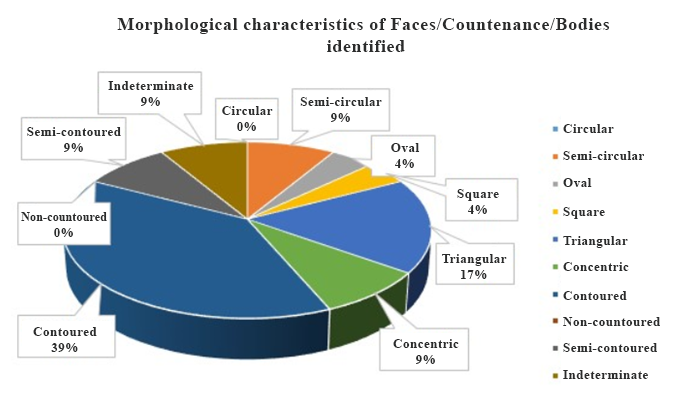

On the other hand, the realistic/naturalistic11 representative features correspond to both human faces and whole bodies with specific characteristics between them, a greater percentage of elements related to faces / faces with contour was determined in a (39%), in addition, a (37%) of the sample corresponds to triangular-shaped faces / faces observing likewise (9%) in semi-contour, semi-circular (9%) designs and in indeterminate designs with (9%). Then the oval designs (4%) and square designs (4%) are in order.

Graph 3. Frequency of the characteristics identified in faces, face and bodies analyzed. Source: The Author

In turn, the features identified in the previous elements are characterized by mostly oval eyes (28%) and circular eyes (20%); while there is a predominance of linear mouth (16%) followed in the order of oval mouth (12%) as well as circular mouth (12%) and finally (4%) responds to those designs with visible facial elements. On the previous basis and trying to identify more detailed aspects of facial features or attractors there are (36%) of the motives in motion, (29%) in a state of amazement, (21%) in contemplative position and (14%) with a feature or in animation state.

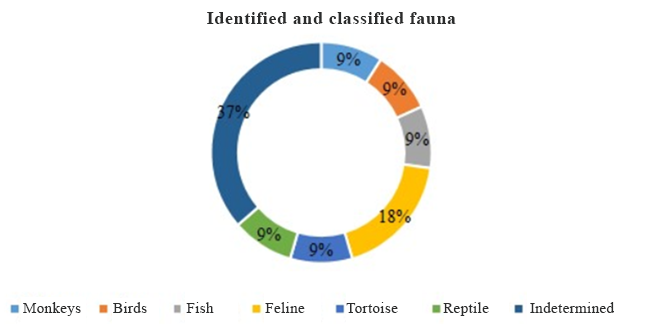

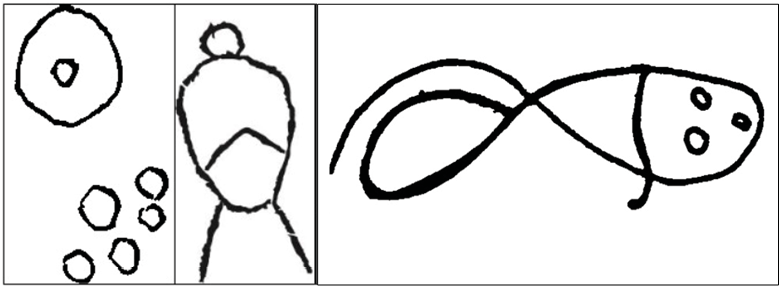

Regarding the analysis of the zoomorphic elements, these reflect predominant motifs with indeterminate designs (37%), followed by motifs with feline characteristics (18%), and then in the order are the motifs with characteristics of monkeys (9%), birds (9%), turtle (9%), fish (9%) and reptiles (9%).

Graph 4. Statistical graphing of the characteristics of the identified fauna motifs. Source: The Author

In most cases, the raw material on which the spellings were made corresponds to basaltic rocks of varying sizes of the geological province of the Atlantic Coast, which naturally appear in the area and which, according to the motive distribution observations in their entirety they were carved both in the center of the rock and sides of these.

Integrate: a pre-iconographic synthesis.

The basic manufacturing technique identified is that of low relief in the majority of the sample but also, the stroke technique12 was applied as well as at least 7 inscriptions from the territory of Santa Fe, whose rocky surface shows yellowing pigmentation, show / reddish and white.

Iconologically what meanings convey the analyzed motives?

While this study indeed uses methodological approaches to art history, also, due to the characteristics of the object of study it is essential to retake the concept of style that can be understood as “the particularity of action and meaning that is built up within an historical context” (Hodder, 1985: 10), as suggested by the iconological analysis carried out on this occasion referring to the realistic and abstract units that express in turn important sub-categories of action and significance constructed within a specific human context , animal, geometric and possibly related to geometric events defined morphologically by the frequent use of lines and that synthesizes a thoughtful abstraction on the part of the creator of the reasons because that set of norms determined by a system of know-power define a particular form of graphic inscription, transforming it into the material concretion of such system (Foucault, 1992). Thus, for example, frequently in other latitudes of the world the geometric element attends to aspects such as delimitation of areas, volumes (width, height, depth or simple shapes), such that the line that appears (in the image 10 above), seems to determine a kind of arrow with a high degree of work and cognitive orientation according to its morphological characteristic.

Another important reason is the straight line (image 14), which by its features seems to be linked to extension or point of separation and that eventually the reason analyzed for being located in the coasts of the Coco River seems to arouse some interest on the part of its creators for graphing forms relative to the immediate water resource, that is, when analyzing the style as a construct determined by a system of knowledge-power, the fact of different ways of being in the world is implicit, and therefore of understanding it, they generate dissimilar cave expressions in its constructive norms (Troncoso, 2003, p.212). As long as the vertical or diagonal line figuratively attends to a state of warmth, firmness or the possibility of movement with a tendency to grow, but not only to the positive, but also, it has an inverse meaning (offspring, tragedy, threat).

Note at the top a documented petroglyph in the coconut river floods by Edward Conzemius, 1984: 104 in his book “Ethnographic Study on the Miskito and Sumus Indians of Honduras and Nicaragua”; Below aerial photography of it. Source: google.com

With respect to the vertical line and curve as geometry, it is possible to add a last comment referring to the (image 10) located in the community of Santa Fe, although it is true that most of these iconographies have been documented as part of the category and subcategory abstract, the panel offers the singular and quite a suggestive perspective because a kind of zoomorphic ideogram is observed at the left end of the rock and in the center of it an anthropomorphic element with semi-flexed feet, a straight line in the center that defines the silhouette of the body, a kind of curvature that defines arms with the particular that the anthropomorphic element suggested seems to have figuratively on its right arm a projectile point; however, these types of interpretations are only preliminary approximations but in fact, “only when we hypothesize about the subjective meanings present in the mind of a human community of the past can we begin to make archeology” (Hodder, 1994, p.95) .

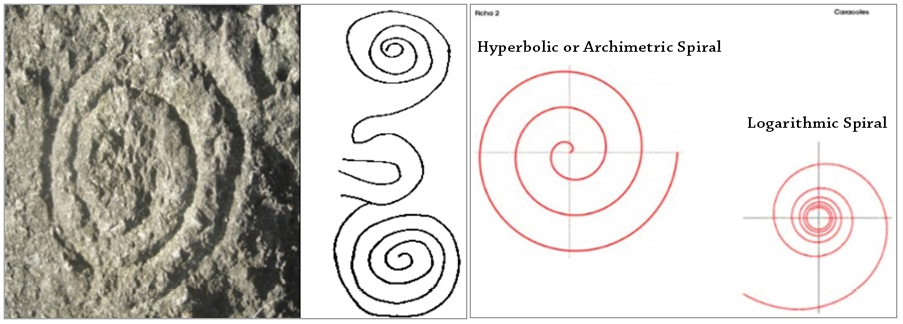

On their behalf, the so-called spiral engravings are “symbolic representations of water” (Manzanilla, 2006, p.124), morphologically it is a curve drawn by a moving point and this revolves around a fixed point eventually linked to rotational movements and translation or cyclical process, growth or expansion; in the analysis two types of simple spirals were identified and those that reached at least more than 2 turns or double divergent or hyperbolic13, term proposed by the mathematician Archimedes Syracuse (287 BC - 212 BC) that according to various latitudes, culture and theorists the meaning varies but without losing its essence of “cycle” and symbolically linked to “born-die-reborn”, in addition, to attend to the concept of growth, expansion and cosmic energy, depending on the culture in which it has been used. For the ancient inhabitants of Ireland, the spiral was used to represent the Sun (https://matematicasiesoja.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/espiralesarte.pdf)

Simple spiral documented in the municipality of Rosita; double or divergent spiral located in San Jerónimo and illustration proposed by the mathematician Archimedes that allows interpreting the engravings analyzed in this opportunity from geometric elements. Source: González and Taylor, 2009/google.com

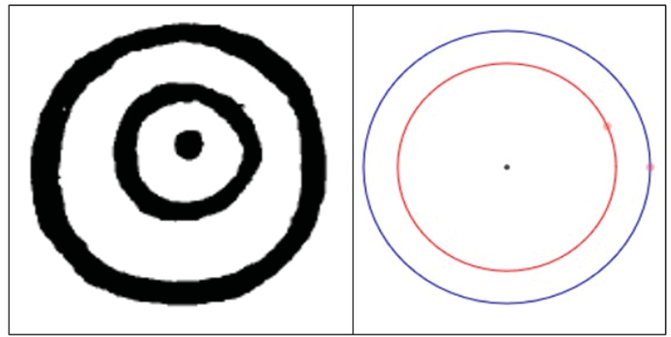

Additionally, always based on the geometric lines with its zigzag variant, it shows undulations and its presence as part of the rock art studied in the territories of Santa Fe and San Alberto in the Coco River, they seem to represent either an admiration to the breakers of the river due to the sinuousness of the motive or veneration for graphically representing the ray that is usually made following a zigzag-shaped scheme, that is, incoming and outgoing angles that denote movement, in particular the zigzag lines they represented rain, water, river or snake because of their kinship with the wavy line (Golan, 1994, p.84 cited by Kolpakova, 2009, p.96). Meanwhile, the point within the circle or call it a concentric circle is still abstract and on it there are countless interpretations about it, among them it seems to reveal a cult of the sun, others that indicate that the point is the (sun) and the circle the (universe) or linked to a symbol of fertilizing power.

Petroglyph documented in the floodwaters of the Coco River by Edward Conzemius, 1984: 104 in his book "Ethnographic Study on the Miskito and Sumus Indians of Honduras and Nicaragua" and illustration that guides a geometric alignment of the motif. Source: google.com

As for the above and the possibility of performing a type of ethnographic parallelism from the cosmogony of the Sumus Indians, the conception of the sun and the moon as brothers is widespread in the area; many Chibcha peoples present it (Constenla, 1990, p.70), in fact in myths and legends of this culture, the number two is presented as the magic number among the Sumus: two are the creators, two are the Ditalyang (bosses, guides), two brothers caused the great flood, in two hills, the Yaluk and Aluk performed the initiation rites (...), equally astronomical elements occurred were represented in stone, perhaps this is because in the “Patuka River, which the sums call Matuka, the eclipses of the moon used to cause a great sensation in people’s spirits.

When the phenomenon began, children and adults got up, lit big fires and made loud demonstrations playing drums, banging cans or any other object to conjure up the possible misfortunes that loomed over the tribe. A kind of struggle between good and evil, between light and darkness, and others believed that a tiger was eating the moon was coming in this event. (Arguedas, 1992, p.55-56)

Something similar happens with the (image 21) defined as soliform (Manzanilla, 2018, p.41), apparently, iconographically, it refers to two bodies that therefore have the same center as the other, as well as their axis or origin. Special attention deserves (image 22), which seems to have some degree of affinity potentially with a character with outstretched arms that we do not know exactly about the context of the same, so far we know that the specimen comes from the Kirwas community in the river’s streams Coco (above) and this appears together with at least five to six reasons reported by Edward Conzemius (1892-1931), in his book Ethnographic Study on the Miskitos and Sumos of Honduras and Nicaragua, which according to the annotations of the Luxembourg ethnologist and linguist externalizes that pictographs can be observed on the rocks that occupy the bed of almost all the great rivers, especially among streams and waterfalls. They must have been sculpted many centuries ago, because they are quite worn out by water (...), and with respect to the sculptured figures they consist mainly of very curious and difficult to identify representations sometimes represent human figures, but mostly they offer animal drawings, jaguars, lizards, monkeys, frogs, turtles and snakes. Occasionally geometric figures are observed, such as spirals and scrolls, but the floral designs are remarkably absent (...) and finally, unknown about the authors of these pictographs, what it does take for granted is that both Miskitus and Sumus unanimously declare that such work is the product of evil spirits (Walasa), in times when the rocks were still “soft”, (Conzemius, 2004, p.203-105).

Reason with anthropomorphic characteristics and elements linked to the sun; Engraved with anthropomorphic details of extended arms from Kirwas, Coco River, in the RACCN. Source: González and Taylor, 2009.

That symbolism and language that the author gathers in his experience in the area can perhaps be understood in simple words when Edward Taylor (1801-1868) quoted by (Sperber, 1988: 22), points out that “the primitive man, reflecting on the experience of the dream, would have inferred from it the notion of an immaterial entity, the “soul”, and would have immediately attributed it to other beings, animals and even inanimate objects, to finally give it an existence independent of all material support, in the form of “spirits.”

Having made the above considerations and in the search to define the signifiers of the two expressions of stone art (petrogravure and pictographs) we have noted the uniqueness of the concentric motif in other regions surrounding Nicaragua, (in addition, from the Kirwas community too, there is another similar example in the community of Santa Fe, that eventually, the symbology seems to always have a mythological connection with the star “Venus” this due to the morphological characteristics of a kind of cosmogram14 (representation of the four directions and the center figured by the symbol cross), being in this way rock art a form of writing, communication and art (Acuña, 2018, p.2).

Mythological connection with the star Venus; in the order of the Mexican Calendar, petroglyph in the abundance of the Coco River by Edward Conzemius, in his book “Ethnographic Study on the Miskito and Sumus Indians of Honduras and Nicaragua” and Copador polychrome ceramics (600-900 AD), documented in archaeological contexts of The Savior. Source: Mexican Archeology / Hugo Iván Chávez.

The sign has been identified from Mexico to Argentina, for example, it appears in the Mexican calendar or in the case of Copador polychrome ceramic (600-900 AD), from El Salvador, so it seems that this symbol had several symbolic connotations implied and had a presence in much of America as suggested by Salvadoran archaeologist Hugo Iván Chávez (personal communication), in fact the Maya identified Venus with a specific symbol, which is found repeatedly in the Dresden Code and in some references from Madrid, Paris, Borgia (Sánchez, 2008, p.2).

The schematization of the human body and the zoomorphic theme

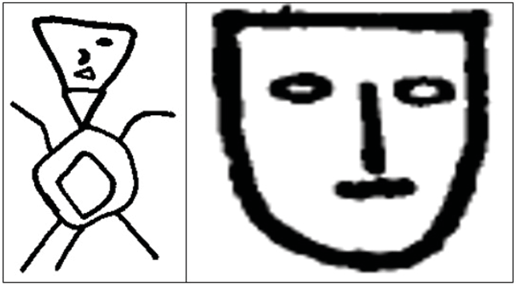

The group and subgroup of anthropomorphic representations is characterized by a good number of faces and whole bodies, that is, schematization of the human body with specific characteristics (head, eyes, nose, and mouth, upper and lower extremities) as in the case of images 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 22 and 23.

Petrogravure with characteristic of officiating, a human face with geometric morphology and in movement and documented engraving in the coasts of the Coco River by Edward Conzemius, 1984: 104 in his book “Ethnographic Study on the Miskito and Sumus Indians of Honduras and Nicaragua. “ Source: González and Taylor, 2009.

In particular, the motif 26 morphologically has a triangle that defines the head and a straight line that begins at the bottom of said geometry that extends downward in vertical orientation that define on the one hand, arms at the top of the motif and in its bottom feet with concentric circle in the center or stomach, like the image 23 described with attire (hat) that bears the human figure and composed of a triangle that defines the head and a circumference that determines a kind of stomach bulging to the Like two straight lines at the ends that make us understand that the character is with open arms and another 2 vertical lines that define arms and feet that can be hypothetically interpreted as a kind of officiants or “owners of special faculties” (Rizo, 1993, p.38), this because of the attire that one of them wears that points to differential access to certain types of goods and on the other hand symbolize the human figure in various ways that in any case:

() An object that is mediated by a figure is, of course, converted into representation. Therefore, the representation is closely related to the object’s referent. These objects within a cultural context refer to a type of knowledge that relates to what the subjects think and how they organize their life. (Villar and Ramírez, 2014: 54)

Another of the attractive reasons is the image 4 that is linked to the mythology or deity of the god of rain, which is arranged by a kind of square that defines the head and where inside it is possible to appreciate 2 points and circles that They need eyes that in turn are determined by 2 sinuous lines that admit a kind of tear and then a vertical line that defines the nose and a square that needs the mouth, referring to the design.

Image 27 has an affinity with a kind of mask about the human face determined by 2 empty circles that define eyes, 1 vertical line that requires a nose and another horizontal line that orients the position of the mouth. On the use of graphic representation in stone, it has been practiced since then “in all peoples there is a mimetic concern to disguise emotions, exalt them, deface them or invent them” (Matillo, 1981, p.14).

Drawings of motifs that reflect zoomorphic elements including feline tread, turtle silhouette and an element linked to a fish. Source: González and Taylor, 2009.

The zoomorphic figurative elements are characterized by evoking or contemplating nature’s own scenes, particularly their fauna, that is, the analysis collects an inventory of the local fauna defined from their morphological structure, including a stylized monkey silhouette and determined to have a “V” shape (image 6), which suggests the shape of eyebrows and other 2 circular or concentric elements (spirals) of at least 2 turns that orient the mouth of the suggested species. Other elements that characterize the local fauna is the identification of two species of feline both face and limbs (image 8 and 28), as well as two aquatic figures one perfectly linked to a turtle (image 29), with a circumference that determines the structure main motif and finally, a fish (image 30), with the presence of geometric elements. Therefore, to this point, the parallels are based, in many cases, on horizontal geometric models that are the basis for the representation by a part of limbs (hands, feet, legs) and a vertical element that determines the main structure of the various elements described (head-face, eyes, mouth).

Preliminary considerations

An evaluative judgment about the contents of the motives is that they show in general terms two large groups and subgroups of visual attractors, those defined as realistic/naturalistic and abstract as frequent and dominant designs that from the analysis determine the line as the essential element in the Their configuration, that is to say, vertical/diagonal/ curved lines are the basis of the elements (anthropomorphic and zoomorphic faces and bodies), while horizontal lines express upper and lower extremities as well as various geometric designs that according to the Ancient symbolic elements described above as the spiral, circles, wavy or zigzag lines directly or indirectly refer to water or rain.

Additionally, the human behavior of ancient societies was full of interactions with the environment (the Nicaraguan Caribbean is characterized by being a region rich in natural resources, rivers, waterfalls, and a varied fauna), which in one way or another transformed for good or for worse the living conditions of these, but also to point out that the designs made in stone either carved or painted reflect precisely those interactions with the environment in the form of thoughts, contemplation, tensions, daily experiences or what we symbolically understand through, of a “sign” or REPRESENTATION (Peirce, 1974, p.1), that which from the theoretical approaches of archeology we would define as styles constructed precisely from a specific historical context and that today we understand them as that ancestral material materialization or simply art cave that expresses ways of being and understanding the world of those societies that They made these works of art in stone. Finally, this is the first installment on an initial characterization of rock art housed in the Autonomous Region of the North Caribbean Coast, knowing that these specimens do not, of course, summarize the whole collection of stone art of the territory, on the contrary, is now when it is most you should investigate in this area and further strengthen the issue of local identity.

Thanks

To Ana Rosa and Patricia Fagoth, as well as Giulia Trobbiani of the TININISKA Cultural Center, to the archeologist, Scarleth Álvarez for the drawings, to geographer Lisseth Blandón in the elaboration of the map presented and to the Miskitu and Sumu ethnic peoples of the RACCN.

Footnotes

1. Within the project of the Research Fund for Cultural Revitalization and Creative Productive Development of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua-RAAN, MDGF1827 (Partnership BICU-UNESCO), the Archaeological Sites Inventory research was carried out in the Municipality of Rosita and its subsequent publication. For more information consult https://www.lamjol.info/index.php/WANI/article/download/884/697

2. Possibly the term has been Castilianized, however, in the dictionary of indigenous toponyms it appears as Kiwas, a pipe that flows into the Coco River, downstream from Kum. Canopy head of the Yulu Tigni river, of the Layasiksa basin, (Incer, 1985, p.112).

3. Both Kirwas and San Alberto are sites with rock art that have not been documented archaeologically, however, due to the nature of the evidence existing in the place, its data is incorporated into the analysis.

4. “From Prinsu, one of the Sumu tribes; pohka, the mountain: the jungle of the Prinzus ”. Ibid., P. 78.

5. The ceramic typology was established by Dr. Wolfgang Haberland at the request of Houwald; the archaeologist suspects that the typology analyzed corresponds to a historical Sumu pottery.

6. A total of 228 archaeological pieces including ceramic (180) and lithic (48).

7. It is headquartered in the city of Puerto Cabezas in charge of the cultural rescue of the Miskitu and Mayangna ethnic groups of the Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua.

8. Among them is Mariela Kitler, a resident of the municipality of Waspán.

9. His analysis is based on the subjectivity of perception.

10. Determined for abstract reasons (lines, points, and others for its structural composition).

11. Integrated by anthropomorphic and zoomorphic motifs both upper and lower faces and extremities.

12. This type of graphic representation on stone usually, besides, to make strokes on the rocky surface were applied mineral substances, the blood of animals or plant substances that served as dyes.

13. Also, it was used to represent the equinoxes when day and night have the same duration

14. The term is addressed by (Torres, 1999, p.18).

Glossary

Anthropomorphic: that has human form or appearance.

Anthropozoomorph: representation that has human and animal characteristics.

Rock art: representation of images and symbols painted, engraved or incised on rocky surfaces in a natural state, reflecting the real and supernatural landscape of the individual or individuals who created it. Includes painting, prints, geoglyphs, and furniture art.

Iconic-Iconography: A sign that is determined by its dynamic object by virtue of its own internal nature, for example, a vision, or the feeling caused by a piece of music considered as a representation of what the composer wanted to express. An icon can also be a diagram (Peirce, 1974, p.1). In this case, the purpose of the iconography is to identify, classify and explain the representations and cave objects.

Pictography: from the Latin pictum, related to painting, and from the Greek grapho, relative to drawing, in a nutshell, they are graphics made on the rocks by applying mineral pigments (coal, clays), animals (blood, bones, fats), or Vegetables (fats, dyes).

Graphic representations: if we look at the rock creations with the eye from the visual arts we find a symbolic visual language, that is, they constitute a system of graphic language resulting from human activities that have been engraved or painted on rocky surfaces.

Size: Breaking fragments of a block of mother rock, by force, percussion or pressure; design cut on a surface with the help of a sharp instrument.

Zoomorfo: that has an animal form or appearance.

Works Cited

Arguedas, G. (1992). La Tradición Oral de los Indígenas Sumos: Características y Temáticas. Revista de Filología y Lingüística XVI. (1):55-96.

Acuña, S. (septiembre de 2018). Arte Rupestre: ¿Escritura, Comunicación o Arte? XIX Coloquio Guatemalteco de Arte Rupestre “Gabriel Morales Castellanos”, Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala.

Conzemius, E. (2004). Estudio Etnográfico sobre los Miskitos y Sumos de Honduras y Nicaragua. Colección cultural centroamericana, serie etnológica, nº 2 1ª ed. Managua, Fundación vida.

Constenla, A. (1990). Introducción al Estudio de las Literaturas Chibchas. Revista de Filología y Lingüística XVI. (1):55-96.

Foucault, M. (1992). Microfísica del Poder. Ediciones de La Piqueta, Barcelona.

González Hodgson K & Taylor, E. (2012). Inventario de Sitios Arqueológicos en el Municipio de Rosita. Retrieved from https://www.lamjol.info/index.php/WANI/article/download/884/697

González Hodgson, K & Taylor, E. (2009). Arqueología en la RAAN: una aproximación al pasado. Tesis monográfica para optar al grado de licenciado en Historia con Orientación en Arqueología. UNAN-Managua. Retrieved from http://repositorio.unan.edu.ni/11132/

Grupo Guatemalteco Investigación de Arte Rupestre. (2009). Glosario de Términos Rupestres. Escuela de Historia de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Nueva Asunción, Guatemala. Retrieved from https://issuu.com/marcelopbarraza/docs/glosario_final_2009

Hodder, I. (1994). Interpretación en Arqueología: corrientes actuales. 2ª ed. Barcelona: Crítica.

Hodder, I. (1985). “Postprocessual Archaeology”, Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory. Pp. 1-26.

Houwald, G. (2003). Mayangna, apuntes sobre la historia de los indígenas Sumus en Centroamérica. Managua: Fundación Vida. 668 pp.

Hurtado, de Mendoza. (2000). Identidad Cultural Mayangna en Nicaragua: Sociedad y Ambiente. Consultores.

Incer, J. (1985). Toponimias Indígenas de Nicaragua. Asociación Libro Libre, San José, Costa Rica. pp 481.

Kolpakova, A. (2009). Símbolos Geométricos en la Cerámica de Izapa, Chiapas. Revista Liminar. Estudios Sociales y Humanísticos Año 7, Vol. VII N°2. Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, México. ISSN:1665-8027. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/liminar/v7n2/v7n2a7.pdf

Manzanilla, R. (2018, septiembre). Introducción al Registro del Arte Rupestre. Dirección de Salvamento Arqueológico del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Ponencia realizada por el autor en el XIX Coloquio Guatemalteco de Arte Rupestre “Gabriel Morales Castellanos”, Nueva Guatemala de la Asunción, Guatemala.

Manzanilla, R. (2006). Los Petrograbados de Palma Sola, México: una reinterpretación. En Volumen I Coloquio de Arte Rupestre (Editado por C. Martínez). Pp. 121-131. Publicación Especial, recopilación de los Coloquios guatemaltecos de Arte Rupestre. Edición Digital.

Matillo, V. (1981). Trilogía Arqueológica Rupestre. Máscaras, Magos y Hechiceros, Danzas y Danzantes en el Arte Rupestre de Nicaragua. Tricentenario de la Obra de la Salle en el Mundo: Managua.

Panofsky, E. (1979). El Significado en las Artes Visuales. 4ª reimpresión. Alianza Editorial.

Peirce, C. (1974). Clasificación de los Signos. En la Ciencia de la Semiótica. Nueva Visión, Buenos Aires. Retrieved from http://www.inpi.edu.ar/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Clasificacion_de_los_signos-Pierce.pdf

Rizo, M. (1993). Mito y Tradición Oral entre los Sumus del río Bambana. Revista WANI N°14.

Sánchez, D. (2008). El Símbolo de Venus en el Arte Rupestre de Perú, Chile y Norte de Argentina. Fundación de Estudios Indigenistas (FUNDESIN). Retrieved from http://rupestreweb.info/venus2.html

Sperber, D. (1988). El Simbolismo en General. Editorial Anthropos. Barcelona.

Torres, A. (1999). La Observación Astronómica en Mesoamérica. Ciencias 54, abril-junio, 16-27. Retrieved from http://www.revistaciencias.unam.mx/images/stories/Articles/54/CNS05403.pdf

Troncoso, A. (2003). Proposición de Estilos para el Arte Rupestre del Valle de Putaendo, curso superior del río Aconcagua”. Chungará (Arica) [online]. Vol. 35, N°2. Pp. 209-231. Retrieved from https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-73562003000200003

Villar, M y Ramírez, J. (2014). El Valor Simbólico de la Imagen Representada. Revista Legado de Arquitectura y Diseño. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4779/477947304004.pdf